Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)

Andrew McIvor, MD, MSc, DCH, FRCP (C), FRCP(E), Professor, Division of Respirology, Department of Medicine, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario; Staff Respirologist at Firestone Institute of Respiratory Health, St. Joseph’s Healthcare, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada[/ultimate_modal]

[/ultimate_modal][ultimate_modal modal_title=”Lecture Slides” btn_txt_color=”#ffffff” modal_on_align=”left” btn_text=”Lecture Slides” modal_size=”block” modal_style=”overlay-fade”][/ultimate_modal][ultimate_modal modal_title=”Patient Brochure” btn_txt_color=”#ffffff” modal_on_align=”left” btn_text=”Patient Brochure” modal_size=”block” modal_style=”overlay-fade”][/ultimate_modal][ultimate_modal modal_title=”Webinar” btn_txt_color=”#ffffff” modal_on_align=”left” btn_text=”Webinar” modal_size=”block” modal_style=”overlay-fade”][/ultimate_modal]

[/ultimate_modal][ultimate_modal modal_title=”Lecture Slides” btn_txt_color=”#ffffff” modal_on_align=”left” btn_text=”Lecture Slides” modal_size=”block” modal_style=”overlay-fade”][/ultimate_modal][ultimate_modal modal_title=”Patient Brochure” btn_txt_color=”#ffffff” modal_on_align=”left” btn_text=”Patient Brochure” modal_size=”block” modal_style=”overlay-fade”][/ultimate_modal][ultimate_modal modal_title=”Webinar” btn_txt_color=”#ffffff” modal_on_align=”left” btn_text=”Webinar” modal_size=”block” modal_style=”overlay-fade”][/ultimate_modal]Definition

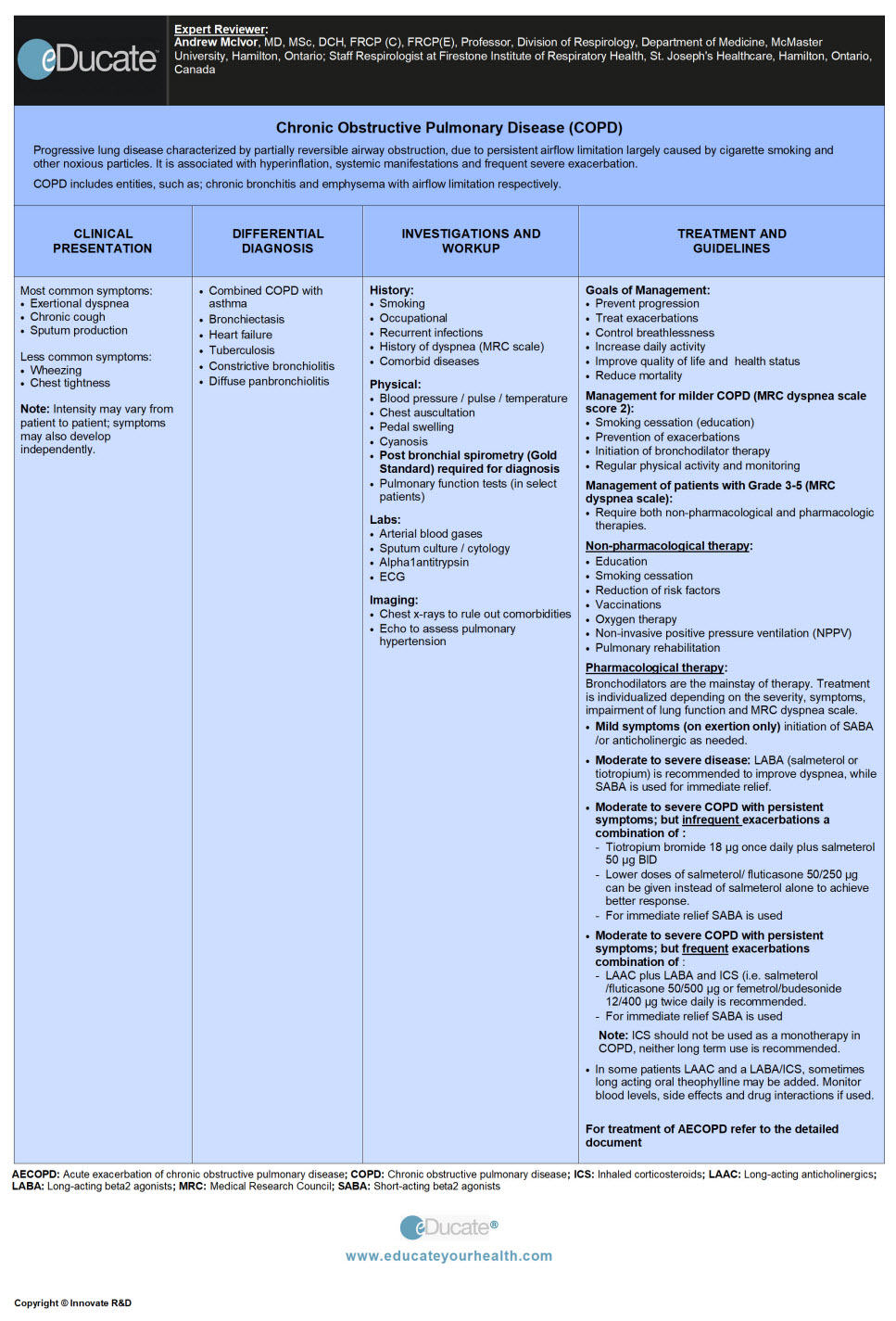

Progressive lung disease characterized by partially reversible airway obstruction, due to persistent airflow limitation largely caused by cigarette smoking and other noxious particles. It is associated with hyperinflation, systemic manifestations and frequent severe exacerbation.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) includes entities, such as; chronic bronchitis and emphysema with airflow limitation respectively.

Patients with asthma having airflow obstruction that does not remit completely are considered to have COPD. The etiology and pathogenesis in such patients may be different from that of patients with chronic bronchitis or emphysema.

- Chronic bronchitis: Productive cough on most days during three consecutive months for more than two successive years in a patient in whom other causes of chronic cough (e.g. bronchiectasis) have been excluded. It may precede or follow the development of airflow limitation

- Emphysema: Parenchymal destruction of lung leading to loss of elastic recoil and airway collapse, followed by lung hyperinflation, airflow limitation, and air trapping. Typically air spaces enlarge and develop bullae

Etiology

- Presence of significant smoking history with:

- Progressive exertional dyspnea

- Cough and/or sputum production

- Frequent respiratory tract infections

- Exposure to passive cigarette smoke

- Air pollution

- Occupational dust (e.g. mineral dust, cotton dust)

- Inhaled chemicals (e.g. cadmium)

- Genetic factors:

- Genetic predisposition plus environmental factors required for COPD as evidenced by the observation that not all smokers develop COPD

- More than 30 genetic variants have been found to be associated with COPD; most potent of them is alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, also an important cause of emphysema in non-smokers

Risk factors:

- Cigarette smoking (an inflammatory trigger)

- Occupational exposures

- Air pollution

- Lung growth during the gestational period and early exposure to smoke and noxious particles in life, may increase the risk of developing COPD

- Age is considered one of the risk factor; however, it’s unclear whether healthy aging is a risk factor or the age reflects the sum of total exposures throughout the life leading to COPD

- Socioeconomic status

- Lung infections

- Chronic bronchitis

- Asthma/ bronchial hyperactivity

Epidemiology

- Fourth leading cause of death

- Predicted third leading cause worldwide by 2020

- Prevalence: Increases with age

- 55 to 64 years, 4.6% – (35-79 years, 4.0%)

- 65 to 74 years, 5.0%

- 75 years or above, 6.8%

- Male to Female ratio: Same after the age of 65 years

References:

- O’Donnell DE, Hernandez P, Kaplan A, et al. Canadian Thoracic Society recommendations for management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease-2008 update – highlights for primary care. Can Respir J. 2008 Jan-Feb; 15(Suppl A): 1A-8A

- The Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease updated 2014 (www.goldcopd.org)

Pathophysiology

The pathological change that occurs in COPD is as follows:

- Chronic inflammation

- Increased number of inflammatory cell type

- Structural changes resulting from repeat injury and repair process

The pathologic changes affect:

- Airways

- Lung parenchyma

- Pulmonary vasculature

Clinical Presentation

Most common symptoms:

- Chronic or progressive dyspnea

- Chronic cough

- Sputum production

Less common symptoms:

- Wheezing/ chest tightness

- Additional features in severe disease, such as; weight loss, anorexia, fatigue are common and can be important sign of other diseases

Note: Intensity may vary from patient to patient; symptoms may also develop independently; there is often a history of exposure to risk factors.

There are 3 sets of patients who commonly present as follows:

- Individuals with sedentary lifestyle: Few complaints and so require careful probing to reach correct diagnosis. These patients may avoid symptoms unknowingly by limiting their daily activity, but will complain of fatigue

- Individuals who present with dyspnea or chronic cough with or without sputum: The symptoms gradual increase in intensity e.g. exertional dyspnea progressing to dyspnea at rest

- Individuals with episodes of intermittent symptoms including less common ones: May be easily confused with asthma

Differential Diagnosis

The main differential is asthma either alone or combined with COPD.

Typically any 3 of the cardinal symptoms (dyspnea, cough, sputum production) at a later age with persistent airflow limitation on pulmonary function test forms the list of differential as follows:

1) Differentiating factors of Asthma and COPD

2) Combined COPD with Asthma:

- Chronic asthmatic plus smoking history may have asthma combined with COPD

- These patients benefit from combined therapy for both conditions

- If an asthma component is predominant then the use of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) is justified

3) Bronchiectasis:

- Patient presents with large volume of purulent sputum, associated recurrent infections

- Clinical features overlap with COPD

- Chest x-ray/ CT scan reveal bronchial dilation and wall thickening

- Differentiated from COPD on the basis of radiographic findings and large volume of sputum production

4) Heart failure:

- Common cause of dyspnea at the later age

- Wheezing and chest tightness may occur due to fluid overload in failing heart

- Pulmonary function test indicate volume restriction

- Differentiated from COPD by the presence of fine basilar crackles and radiographic evidence of increased heart size and pulmonary edema

5) Tuberculosis:

- May occur at any age and should be considered in TB endemic areas

- Differentiation is based on the presence of lung infiltrates on chest x-ray and microbiological confirmation

6) Constrictive bronchiolitis:

- Usually occurs at a younger age in the non-smoker

- Stems from inhalational injury or transplant

- Also seen in association with rheumatoid lung or inflammatory bowel disease

- Symptoms include the progressive onset of cough and dyspnea associated with hypoxemia at rest or with exercise

- Hypodense areas observed with CT scan on expiration

7) Diffuse panbronchiolitis:

- Non-smoker; males

- Associated with chronic sinusitis

- Chest x-ray/CT scan show opacities corresponding to thick and dilated bronchial walls with mucus plugs

Investigation and Workup

COPD is often under-diagnosed, and many have an advanced pulmonary impairment at the time of diagnosis. Early diagnosis and smoking cessation are beneficial at all stages.

HISTORY:

A detailed history including:

- Smoking (quantify tobacco consumption)

- Occupation or environmental exposures (inhalational history)

- History of recurrent upper respiratory infections in childhood

- Nasal polyps, allergies, sinusitis, asthma and other respiratory diseases

- Comorbid diseases, such as; CAD, hypertension, glaucoma, osteoporosis, rheumatoid arthritis, anxiety depression etc

- Acute exacerbation is defined as increased severity of symptoms of COPD which may occur sporadically during the course of the disease.

- Family history of COPD

- History of dyspnea using the MRC dyspnea scale (Table no:1)

- Cough and sputum production

- Frequency and severity of exacerbation (i.e. dyspnea, cough, sputum)

- Current medical treatment

- Symptoms such as pedal swelling, weight loss, maybe the complication of COPD and should be carefully assessed

PHYSICAL EXAM:

Important but not diagnostic in COPD; should always be undertaken to evaluate possible comorbidities. The disease takes years to develop, patients who are smokers have smoked >20 cigarettes/day for >20 years. Symptoms are variable in intensity examination should include:

- Blood pressure, pulse, temperature

- Chest auscultation for heart sound, wheeze, crackles, effusion

- Chest percussion: increased resonance due to hyperinflation

- Peripheral cyanosis

- Check for swelling in the periphery

- Spirometry (postbronchodilator) to assess the severity of the disease

The Canadian Lung Association suggests, that patients who are ≥40 years and who are current or ex-smokers should undergo spirometric testing if any one of the following answers is in yes:

– Disease severity:

Management decisions should be individualized and guided by the severity of symptoms and disability.

Ideally one should consider evaluating all the variables of impairment in addition to spirometry to stratify the disease severity and should include:

- Current level of patient’s symptoms

- Functional impairment

- Impaired activity (disability)

- Limitations in participating (handicap)

- Severity of spirometric abnormality

- Exacerbation risk

- Presence of comorbidities

– Assessment of symptoms:

Previously for COPD assessment mMRC dyspnea scale was considered adequate. However, after recognition of multiple symptomatic effects of COPD, a comprehensive symptom assessment is recommended, and includes the following

- COPD Assessments Test (CAT): A shorter version of Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire (CRQ). It is 8 items unidimensional measure of health status impairment in COPD. The score range from 0-40. Available at (www.catestonline.org)

- COPD Control Questionnaire (CCQ): A shorter version of St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ). A 10 item self-administered questionnaire developed to measure clinical control in patients with COPD. Although the concept of “control” remains controversial, however; it is short and easy to administer. Available at (www.ccq.nl)

- The Dyspnea Scale:

Choice of score cut points for the purpose of treatment: SGRQ scores less than 25 are uncommon in diagnosed COPD patients and ≥25 are not seen in healthy persons

Classification of COPD severity by symptom and disability

– Spirometry:

Is used to measure the airflow limitation, however; mass screening of asymptomatic individuals not recommended, but targeted spirometric testing to establish the early diagnosis is recommended.

Although spirometry is essential to make a diagnosis of COPD, it may not rule out asthma, particularly in elderly patients with asthma, in whom the symptoms of fixed-airflow obstruction can appear similar to those of COPD.

Diagnostic criteria for COPD:

“A postbronchodilator FEV1/FVC ratio less than 0.7 confirms the presence of airway obstruction that is not fully reversible”

Classification of COPD by impairment of lung function:

Assessment of exacerbations:

An acute event characterized by worsening of symptoms, and leads to change in medication. Worsening of airflow limitation is associated with increase in prevalence of exacerbation and risk of death. Acute exacerbation leading to hospitalization is associated with poor prognosis and risk of death.

Assessment of comorbidities:

The existence of COPD increases the risk of other diseases. Comorbidities may occur in patients with mild, moderate or severe airflow limitation. The disease itself has multiple systemic effects including weight loss, nutritional abnormalities, and skeletal muscle dysfunction.

Other frequently occurring comorbidities are as follows:

* Cardiovascular diseases

* Metabolic syndrome

* Osteoporosis

* Depression

* Lung cancer

Combined COPD Assessment:

- Comprehensive measure of symptoms with CAT

- Assessment of breathlessness with mMRC

- Risk of exacerbation by following 3 methods

- Population based method using GOLD spirometry classification

- Based on the history of exacerbations

- History of hospitalization due to exacerbation

Note: In case there is a discrepancy between these criteria’s the highest risk group should be used, to decide further management.

– GOLD COPD Symptom/risk evaluation:

Additional Investigations:

Laboratory:

Oximetry and ABG:

- Oximetry used for oxygen saturation

- If peripheral saturation is <92% ABGs are done

- FEV1 <35% of predicted or clinical signs suggestive of respiratory failure or right heart failure

Lung volumes and diffusing capacity:

- Body plethysmography or helium dilution lung volume measurement: Document gas trapping (↑residual volume) from early in the disease, as well as the airflow limitation worsening (↑ total lung capacity) as it occurs

- Measurement of diffusing capacity (DLco): Is helpful in patients with breathlessness that may seem out of proportion with the degree of airflow limitation

Alpha 1 antitrypsin level:

- WHO recommends that COPD patients from areas with high prevalence of Alpha 1 antitrypsin deficiency should be screened for this genetic disorder. Typically such patients present much earlier in life (<45 years), and with a family history

Exercise testing:

- Objectively measured exercise self-assessment for progressive impairment or during incremental exercise testing in the laboratory, indicates prognosis and current health status

The BODE method gives a composite score:

- A comprehensive grading system in conjunction with FEV1, is a survival prediction, and stands for

B= Body mass index

O= Airflow obstruction

D=Dyspnea

E= Exercise capacity

Imaging:

- Plain X-rays help assess alternative diagnosis and presence of comorbidities

- Peribronchial and perivascular markings in chronic bronchitis

- Flat diaphragm in hyperinflation

- Parenchymal bullae in emphysema

- Rule out lung cancer, bronchiectasis, and tuberculosis

- CT scan chest:

- Not routinely done, and is only helpful if there is a doubt about the diagnosis of COPD

Prognostic Factors:

In addition to the forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), various factors and outcomes are thought to influence the prognosis of COPD and include:

- Cigarette smoking

- Airways responsiveness

- Age

- Nutritional status

- Frequency, severity of exacerbations and hospitalization

- Long term use of oxygen

- Use of oral corticosteroids

- Gas exchange abnormalities

- Low body mass index (BMI ≤21)

- Elevated C-reactive protein (>3 mg/L)

- Peak oxygen consumption (VO2), measured by cardiopulmonary exercise testing

- Presence of comorbidities

- Presence of emphysema

- Presence of pulmonary hypertension

Treatment

Goals of Management:

- Prevent progression of the disease

- Treat exacerbations to decrease frequency and severity

- Control breathlessness and other respiratory symptoms

- Increase daily activity

- Improve quality of life and health status

- Reduce mortality

The management for milder COPD (MRC dyspnea scale score 2):

Usually involves

1) Smoking cessation with educational programs

2) Prevention of exacerbations (vaccination)

3) Initiation of bronchodilator therapy

4) Regular physical activity

5) Close monitoring of disease status

Management of patients with Grade 3-5 (MRC dyspnea scale):

These individuals are often disabled and require both non-pharmacological and pharmacologic therapies.

NON-PHARMACOLOGICAL THERAPY:

1) Education:

2) Smoking cessation:

It is recommended that minimal intervention lasting for at least ≤3 minutes should be offered to every smoker. It is known that intensive counseling with pharmacotherapy results in higher quit rates and should be used whenever possible.

Nicotine replacement therapy in combination with antidepressant (bupropion) doubles the cessation rates.

3) Reduction of risk factors:

Occupational/environmental/pollutant exposures: Advise to relocate or change occupation. If the latter is not possible then avoid of inhalational exposure (use of mask) during work

4) Vaccination:

Should be offered to patients with stable COPD. It is recommended to give annual influenza vaccines provided there are no contraindications. Pneumococcal vaccines should be given at least once in the life time and in high risk patients and consider repeating the vaccine in 5-10 years.

5) Oxygen therapy:

Maintenance of O2 saturation ≥90% for ≥15hr/day is recommended in cases of severe hypoxemia (PaO2 55 mmHg or less) or if PaO2 <60 mmHg in the presence ankle edema, cor pulmonale or increased Hematocrit >56%.

6) Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation (NPPV):

- No benefit in patients with milder exacerbations

- Not recommended in stable COPD patients with hypercapnia

7) Pulmonary rehabilitation (PR):

- Individuals with COPD suffer mostly by activity limitation and shortness of breath

- Pulmonary rehabilitation helps patients with respiratory symptoms despite being on optimal treatment

- Includes patient assessment, exercise training, self-management education to achieve behavior changes, and psychosocial support

Benefits of PR in COPD:

- – Improves symptoms (activity limitation,

- breathlessness) and hence quality of life

- – Reduce exacerbations and hence hospitalizations,

- healthcare cost, anxiety and depression

Comprehensive PR:

- – Can be done on an in-patient or outpatient (home)

- setting

- – A typical program lasts from 6-12 weeks, with

- patients taking part in self-management patient

- education and doing 2-5 exercise sessions per week

- – Usually, both aerobic training (AT) and resistant

- training (RT) for upper and lower extremities are

- recommended using different modalities

- – PR is recommended within 1 month of acute

- exacerbation of COPD

Reference: Marciniuk DD, Brooks D, Butcher S et al. Canadian thoracic Society COPD Committee Expert Working Group. Optimizing pulmonary rehabilitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease- practical issues. Can Respir J 2010;17(4): 159-168.

[/cq_vc_tab_item][cq_vc_tab_item tabtitle=”Pharmacologic therapy”]PHARMACOLOGICAL THERAPY:

- Bronchodilators are the mainstay of therapy in COPD

- Bronchodilators improve airflow limitation, and are chosen depending on the severity of the disease according to the symptoms, impairment of lung function and MRC dyspnea scale

- Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) alone, is not recommended in COPD and are less effective than combination therapy with ICS plus long-acting beta adregenic agonist (LABA)

Drug Therapy Recommendations CTS 2008:

- Mild symptoms (on exertion only): Short-acting beta-2 agonists or anticholinergic alone or in combination) as needed

- Moderate to severe airflow obstruction: Long-acting bronchodilators (tiotropium or salmeterol) is recommended to improve dyspnea, while short-acting beta2 agonists are used for immediate relief

- Moderate to severe COPD with persistent symptoms; but infrequent exacerbations a combination of:

- Tiotropium bromide 18 µg once daily plus salmeterol 50 µg twice daily is recommended

- Lower doses of salmeterol/ fluticasone 50/250 µg can be given instead of salmeterol alone to achieve better response

- For immediate relief, short-acting beta-2 agonists can be used

- Moderate to severe COPD with persistent symptoms; but frequent exacerbations a combination of:

- Long-acting anticholinergic (LAAC) plus long-acting beta-2 agonists (LABA) and ICS (i.e. salmeterol/ fluticasone 50/500 µg or femetrol/ budesonide 12/400 µg twice daily is recommended

- For immediate relief, short-acting beta-2 agonists can be used

- In some patients, LAAC and a LABA/ICS, sometimes long-acting oral theophylline may be added. Monitor blood levels, side effects, and drug interactions if used.

– CTS pharmacotherapeutic options (2008):

Drug Therapy Recommendations GOLD 2014:

The GOLD therapeutic strategy is similar to the approach recommended by the Canadian Thoracic Society (CTS) which is based on both spirometry and the Medical Research Council dyspnea grade.

However, the new GOLD grouping produces an uneven split of the COPD population, and its prognostic validity to predict time-to-death does not differ from the old GOLD staging based on spirometry criteria alone. The GOLD grouping also requires the use of questionnaires that are not widely utilized by physicians.

GOLD recommends that ICS/LABA combinations are restricted to patients in GOLD group C and group D. While the use of ICS/LABA combinations in appropriate patients is effective, ICS are often prescribed inappropriately to patients with more moderate disease.

– GOLD COPD symptom/risk evaluation:

– GOLD therapeutic strategies:

Alpha1 anti-trypsin (AAT) deficiency:

Patents with FEV1 >35% and <65% predicted; and are on optimal medical therapy and still continue to show decline in FEV1; are not recommended for replacement therapy.

Reference: A registry of patients with severe deficiency of alpha 1-antitrypsin. Design and methods. The Alpha 1-Antitrypsin Deficiency Registry Study Group. Chest;106(4);1223-32

Upcoming therapeutic agents include:

- PDE4 inhibitors

- PDE-4 inhibitors, single-molecule muscarinic antagonist/β2-agonists (MABAs)

- TNF-α antagonists, N-acetylcysteine, and its derivatives

- CCR1 chemokine receptor antagonists

- p38 MAPK inhibitors

- M3-selective muscarinic antagonists

- Bifunctional muscarinic antagonist/β2 agonists

The PDE-4 inhibitor (roflumilast) is recommended by GOLD (in combination with a long-acting bronchodilator) to reduce exacerbations in patients with chronic bronchitis, severe and very severe COPD, and frequent exacerbations inadequately controlled by long-acting bronchodilators.

SURGICAL OPTIONS:

1) Lung volume reduction surgery (LVRS):

There have been multiple clinical trials which have reported evidence supporting LVRS to be an effective option in the management of COPD provided they meet the selection criteria as shown below:

– Selection criteria for lung reduction surgery:

2) Lung transplant in COPD:

Patients are considered for lung transplant if they meet the following criteria:

- FEV1 <25% predicted (without reversibility)

- Partial pressure of arterial CO2 >55 mmHg or

- Elevated pulmonary artery pressure (PAP)

End of Life issues:

- It is the physician’s responsibility to discuss end of life issues and provide support

- Elderly patients with severe airflow obstruction (FEV1 <35% predicted) with poor functional status, recurrent AECOPD, and pulmonary hypertension, who are at risk of death should be guided and supported to deal with the end of life care

Acute exacerbation of COPD (AECOPD):

Persistent worsening of dyspnea, cough and sputum production, requiring increase and/or addition in the use of medication is called AECOPD. Worsening is defined as a change from baseline lasting up to 48 hrs or more. It can be divided into purulent or nonpurulent exacerbation.

Average COPD patient may have 2 exacerbations per year, but is highly variable, 40% may not have it at all. Usually, one-half of these patients are thought to be infectious. Most infections are viral and others are bacterial.

– Strategies to prevent AECOPD:

– Management of AECOPD:

After a detailed history and examination, diagnostic evaluation includes:

- Chest x-ray

- Arterial blood gases in patients with low arterial oxygen saturation on oximetry

- Gram stain and culture in patients presenting with purulent sputum

- Pulmonary function test

Therapy:

- Oxygen saturation: To be maintained at 90% or higher

- Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation (NPPV): Patient with advanced COPD with Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) status or Do Not Intubate can be considered for NPPV. It is recommended to be administered under close cardiopulmonary monitoring in patients with severe exacerbation of COPD (pH = <7.3). Respiratory arrest and hemodynamic instability being an absolute contraindication

- Bronchodilators: Combined short-acting inhaled beta2 agonists (salbutamol, terbutaline, fenoterol) or anticholinergic (ipratropium bromide) should be administered immediately in acute situations through nebulizers

- Corticosteroids: Systemic corticosteroids are indicated in most cases

- Prednisone 30-40 mg per day for 10 to 14 days, is suggested

- Antibiotics: Use is beneficial in patients with purulent exacerbations, which are divided into simple and complicated based on the presence of risk factors as follows:

- FEV1 <50% predicted

- Four or more exacerbations per year

- Ischemic heart disease

- Use of home oxygen

- Chronic oral corticosteroid use

- Antibiotic use in the past 3 months

- Common pathogens in simple purulent exacerbation are:

- Haemophilus influenzae

- Streptococcus pneumoniae

- Moraxella catarrhalis

- In complicated group pathogens including above plus the following may be isolated:

- Klebsiella and other gram-negatives

- Increased probability of beta-lactam resistance

- Choices of antibiotics in AECOPD:

- Amoxicillin: 500 mg PO TID 7-10 days

- Doxycycline: 200 mg PO BID day 1 then 100 mg PO daily for 7-10 days

- Sulfamethoxazole 800 mg/Trimethoprim 160 mg: One tablet PO BID for 7-10 days

- Second generation cephalosporins: Cefuroxime 250-500 mg PO BID for 7-10 days

- Third generation cephalosporins: Cefpodoxime 200 mg PO BID for 10 days

- Extended-spectrum macrolides: Clarithromycin 250-500 mg PO BID for 7-10 days

- Beta-lactam/ beta-lactamase inhibitors: Amoxicillin-clavulanate 500 mg PO TID for 7-10 day

- Fluoroquinolone: Moxifloxacin 400 mg PO daily for 5-10 days

Algorithm: Antibiotic therapy in AECOPD (secondary to oxygen, bronchodilator, and steroid therapy)[/cq_vc_tab_item][cq_vc_tab_item tabtitle=”Medication Dose”]MEDICATIONS:

1) Bronchodilators:

- Short-acting beta2-agonists (SABA)

- Long-acting beta2-agonists (LABA)

- Short-acting anticholinergic (SABD)

- Long-acting anticholinergic (LAAC)

Mechanisms:

- Bronchodilators → decrease smooth muscle tone → Improve lung emptying; reducing hyperinflation with little effect on heart rate

Short-acting beta agonists (SABA):

- Salbutamol (Albuterol called in the USA)

- Levalbuterol

- Terbutaline

Mechanisms:

- These agents improve pulmonary function, dyspnea, and exercise performance

Dose:

Salbutamol (Albuterol in the USA):

Adult:

Bronchospasm

- Oral: 5 mg per dose divided in 2-3 doses/day: Max. 32 mg/day

- Inhaler: 100-200 µg (MDI and DPI) may use 2-4 puff every 20 min for 3 doses to treat an acute exacerbation

- Nebulizer: 2.5-5 mg every 4-6 hrs as needed, diluted in 2-5 mL sterile saline or water. Dilute 0.5 mL (2.5 mg) 0.5% inhalation solution in 1-2.5 mL of NS

* MDI: metered-dose inhaler

* DPI: dry powder inhaler

Levalbuterol: not available in Canada

Adult:

Bronchospasm

- MDI: 45-90 µg as needed

- Nebulizer: 0.21-0.42 mg/ml TID at intervals of 6-8 hrs

Terbutaline/Ipratropium:

Adult:

Bronchospasm

- 400-500 µg (DPI) taken as needed; may repeat after 5 minutes. If needed

- Do not exceed more than 6 doses/24 hrs

Long-acting beta2-agonists (LABA):

- Formoterol

- Indacaterol

- Salmeterol

Mechanisms:

- Is a selective, long-acting (12 hours), beta2-adrenoceptor agonist with a long side-chain which binds to the exo-site of the receptor

Dose:

Formoterol:

Adult:

- 4.2-12 µg (MDI and DPI) every 12 hrs

Indacaterol:

Adult:

- 75-300 µg (DPI) once a day

Salmeterol:

Adult:

- 25-50 µg (MDI and DPI) every 12 hrs

Short-acting anticholinergic (SABD):

- Ipratropium

Mechanisms:

- Inhibits cholinergic receptors in bronchial smooth muscle causing bronchodilator; local application to nasal mucosa inhibits secretions from glands lining the nasal mucosa

Dose:

Adult

- Nebulizer: 0.25-0.5 mg/ml every 20 mins for 3 doses, then as needed for acute exacerbations

- MDI: 20-40 µg 4 times a day; Max. 12 puffs/day

Long-acting anticholinergic (LAAC):

- Aclidinium bromide

- Tiotropium (Spiriva)

Mechanisms:

- Long-acting, antimuscarinic agents, which are often referred to as an anticholinergic. Causes the bronchodilation by competitively and reversibly inhibits the action of acetylcholine and other cholinergic stimuli at type 3 muscarinic (M3) receptors in the bronchial smooth muscle

Dose:

Aclidinium bromide:

Adult

- 400 µg twice daily

Tiotropium:

Adult

- 18 µg (DPI) once daily

2) SABA plus Anticholinergics combination therapy

- Ipratropium/ Fenoterol

- Ipratropium/ Salbutamol

Mechanisms:

- The administration of the above combination results in dilatation of bronchi. The 2 agents complement each other and provide maximal effect with minimal dosage, in turn, reducing the side effects and improving the tolerance in moderate to severe COPD

Dose:

Ipratropium/ Fenoterol (Duovent):

- Nebulizer: Dilute solution of 0.5 mg of ipratropium bromide and 1.25 mg fenoterol hydrobromide in 4 mL of isotonic saline

- MDI: 200/80 µg every 6-8 hrs as needed

Ipratropium/ Salbutamol (Combivent)

- Nebulizer: 0.50 mg/2.5 mg in 2.5 mL of isotonic solution for inhalation

- MDI: 15/75 µg every 6-8 hrs

- Theophylline

Mechanisms:

- The exact mechanism is unknown. However; is responsible for causing bronchodilatation, diuresis, CNS and cardiac stimulation. Blocks phosphodiesterase by increasing gastric acid secretions which increases tissue concentrations of cyclic adenine monophosphate (cAMP) which in turn promotes catecholamine stimulation of lipolysis, glycogenolysis, and gluconeogenesis and induces release of epinephrine from adrenal medulla cells

Dose:

Theophylline:

Considered second line IV in the emergency room in COPD

- Loading dose: ~5.8 mg/kg IV or 5 mg/kg oral. Intension is to achieve serum levels of 10 µg/mL

- Note: Every mg/kg given; the blood level will raise 2 µg/mL

Acute symptom maintenance:

- Adults non-smoker 900 mg/day IV (0.4 mg/kg/hour); in adults >60 years 0.3 mg/kg/hr

Treatment of chronic condition:

- Oral extended release formulation (adult): 200-400 mg PO daily; to be adjusted according to the serum levels

4) Long acting beta2-agonist plus corticosteroids

- Fluticasone/ Salmeterol

- Budesonide/ Formoterol

- Mometasone/ Formoterol

Mechanisms:

- Formoterol, salmeterol relaxes bronchial smooth muscle by selective action on beta2receptors with little effect on heart rate

- Formoterol has both a long-acting and rapid-acting effect.

- Fluticasone, budesonide, and mometasone are corticosteroid which controls the rate of protein synthesis, depresses the migration of polymorphonuclear leukocytes/fibroblasts, and reverses capillary permeability and lysosomes stabilization at the cellular level to prevent or control inflammation.

Dose:

Fluticasone/ Salmeterol (Advair Diskus)

- Diskus type is available in 3 strengths:

- Fluticasone/ Salmeterol: 100 µg/50 µg, 250 µg/50 µg, 500 µg/50 µg

Adult:

- Inhalation: 250 µg/50 µg twice daily or 500 µg/50 µg twice daily

Budesonide/ Formoterol (Symbicort)-only available as a turbuhaler in Canada

Adult DPI– turbuhaler: Budesonide 100 µg plus formoterol 6 µg/inhalation

- Inhalation: 400/12 µg daily is recommended (2 inhalations twice daily)

Mometasone/ Formoterol

Adult

- Inhalation: 10 µg/200 µg or 10 µg/400 µg MDI daily

5) Phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor

- Roflumilast

Mechanisms:

- Selectively inhibit phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE4). The exact mechanism of action of roflumilast is unknown; it is thought to be related to the effects of increased intracellular cyclic AMP in lung cells

Dose:

Roflumilast:

- Oral: 500 µg tablet per day

6) Systemic Corticosteroids in AECOPD

- Prednisone

Mechanisms:

- They have an anti-inflammatory effect through multiple mechanisms. They suppress the body’s immune responses through mechanisms such as reduction of activity and volume of the lymphatic system, decreased immunoglobulin and complement concentrations as well as decreased passage of immune complexes through basement membranes

Systemic corticosteroids are indicated in most cases of AECOPD.

Dose:

Ipratropium/ Fenoterol (Duovent):

- Prednisone 30-40 mg per day for 10 to 14 days, is suggested

[/cq_vc_tab_item][/cq_vc_tabs]

Clinical Trials

Physician Resources

1. Tips for Patient Care

Risk factor management:

- Promote smoking cessation – cigarette smoking leads to frequent hospitalizations due to COPD exacerbations

- If occupational exposure is suspected, ask for details job and workplace environment

- Targeted testing for A1AT deficiency should be considered in diagnosed cases of COPD before the age of 65 years or in patients with smoking history of <20 packs/year

Medications:

- Treatment approach to exacerbations is multifactorial (i.e. infectious or non-infectious). Overuse of on antibiotics may lead to resistance and treatment failure

- Inhaled corticosteroids are not to be used as monotherapy in COPD

- Prolong use of ICS is discouraged

- Monitor serum levels in patients taking theophylline

- Influenza vaccines are recommended annually

- Pneumococcal vaccines are recommended every 5-10 years after the age of 65 years

Social and Stress factors:

- Include family or social support in lifestyle modification, such as; smoking cessation

- Patient should recognize the early signs and symptoms of exacerbations

Physical activity:

- Both aerobic training (AT) and resistant training (RT) for upper and lower extremities

- It is suggested to start pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) within 1 month of acute exacerbation of COPD

2. Scales and Table

References

Core Resources:

- Compendium of Pharmaceuticals and Specialties (CPS). Canadian Pharmacist Association. Toronto: Webcom Inc. 2012

- Day RA, Paul P, Williams B, et al eds. Brunner & Suddarth’s Textbook of Canadian Medical-Surgical Nursing. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2010

- Foster C, Mistry NF, Peddi PF, Sharma S, eds. The Washington Manual of Medical Therapeutics. 33rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010

- Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: (2014 update). Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). www.goldcopd.org

- Gray J, ed. Therapeutic Choices. Canadian Pharmacists Association. 6th ed. Toronto: Webcom Inc. 2011

- Katzung BG, Masters SB, Trevor AJ, eds. Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. 11th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2009

- Longo D, Fauci A, Kasper D, et al. eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 18thed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2011

- McPhee SJ, Papadakis MA, eds. Current Medical Diagnosis & Treatment. 49th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2010

- O’Donnell DE, Aaron,S, Bourbeau J, et al. Canadian Thoracic Society recommendations for management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Can Respir J. 2003;10(Suppl A):5-33A

- O’Donnell DE, Hernandez P, Kaplan A, et al. Canadian Thoracic Society recommendations for management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease-2008 update-highlights for primary care. Can Respir J. 2008 Jan-Feb;15(Suppl A):1A-8A

- Pagana KD, Pagana TJ eds. Mosby’s Diagnostic and Laboratory Test Reference. 9th ed. St. Louis: Elsevier-Mosby; 2009

- Skidmore-Roth L. ed. Mosby’s nursing drug reference. 24th ed. St. Louis: Elsevier-Mosby; 2011

- Skidmore-Roth L. ed. Mosby’s drug guide for nurses. 9th ed. St. Louis: Elsevier-Mosby; 2011

Online Pharmacological Resources:

- e-Therapeutics

- Lexicomp

- RxList

- Epocrates

Journals/Clinical Trials:

- Anthonisen NR, et al. Smoking and lung function of the lung health study participants after 11 years. Am.J.Respir.Crit.Care Med.2002:166:675-9

- Bateman ED, Ferguson GT, Barnes N et al. Dual bronchodilation with QVA149 versus single bronchodilator therapy. 2013 ERJ Express

- doi: 10.1183/09031936.00200212

- Buist AS, McBurnie MA, Vollmer WM, et al (BOLD Collaborative Research Group). International variation in the prevalence of COPD (the BOLD Study): a population-based prevalence study. Lancet. 2007; 370:741

- Calverley PM, Koulouris NG. Flow limitation and dynamic hyperinflation: key concepts in modern respiratory physiology. Eur Respir J. 2005; 25:186

- Calverley P, Anderson J, M.A., Celli B, et al for the TORCH investigators. Salmeterol and Fluticasone Propionate and Survival in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. N Engl J Med 2007;356:775-89

- Ford GT, Chapman KR, Standards Committee of the Canadian Thoracic Society. Alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency: A position statement of the Canadian Thoracic Society. Can Respir J 2001; 8:81-8

- Gershon AS, Warner L, Cascagnette P, et al. Lifetime risk of developing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a longitudinal population study. Lancet. 2011;378:991-6

- John M, Hoernig S, Doehner W,et al. Anemia and Inflammation in COPD. Chest. 2005:127:825-829

- Mahler DA, D’Urzo A, Bateman ED et al on behalf of the INTRUST-1 and INTRUST-2 study investigators. Concurrent use of indacaterol plus tiotropium in patients with COPD provides superior bronchodilation compared with tiotropium alone: a randomized, double-blind comparison. Thorax 2012;67:781-788 doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-20114

- Marciniuk DD, Hernandez MP, Balter M et al. Canadian Thoracic Society COPD Clinical Assembly Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency Expert Working Group. Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency targeted testing and augmentation therapy: A Canadian Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline. Can Respir J 2012;19:109-116

- O’Donnell DE, Revill S, Webb KA. Dynamic hyperinflation and exercise intolerance in COPD. Am J Respir Crit Care Med.2001; 164:770-7

- Parker CM, Vodue N, Aarson SD et al. Physiological changes during symptom recovery from moderate exacerbations of COPD. Eur Respir J 2005; 26:420-8

- Rennard et al. Reduction of exacerbations by the PDE4 inhibitor roflumilast-the importance of defining different subsets of patients with COPD. 2011 Respiratory Research, 12:18 (http://respiratory-research.com/content/12/1/18)

- Sethi S, Murphy TF. Infection in the pathogenesis and course of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2008; 359:2355

- Tashkin PD, Celli B, Senn S et al for the UPLIFT Study Investigators. A 4-Year Trial of Tiotropium in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1543-54

- The Management of Acute Exacerbations of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (AECOPD). Towards Optimized practice (TOP), Alberta clinical practice guidelines, 2006 Update (www.topalbertadoctors.org)

[bellows config_id=”main” menu=”52″]