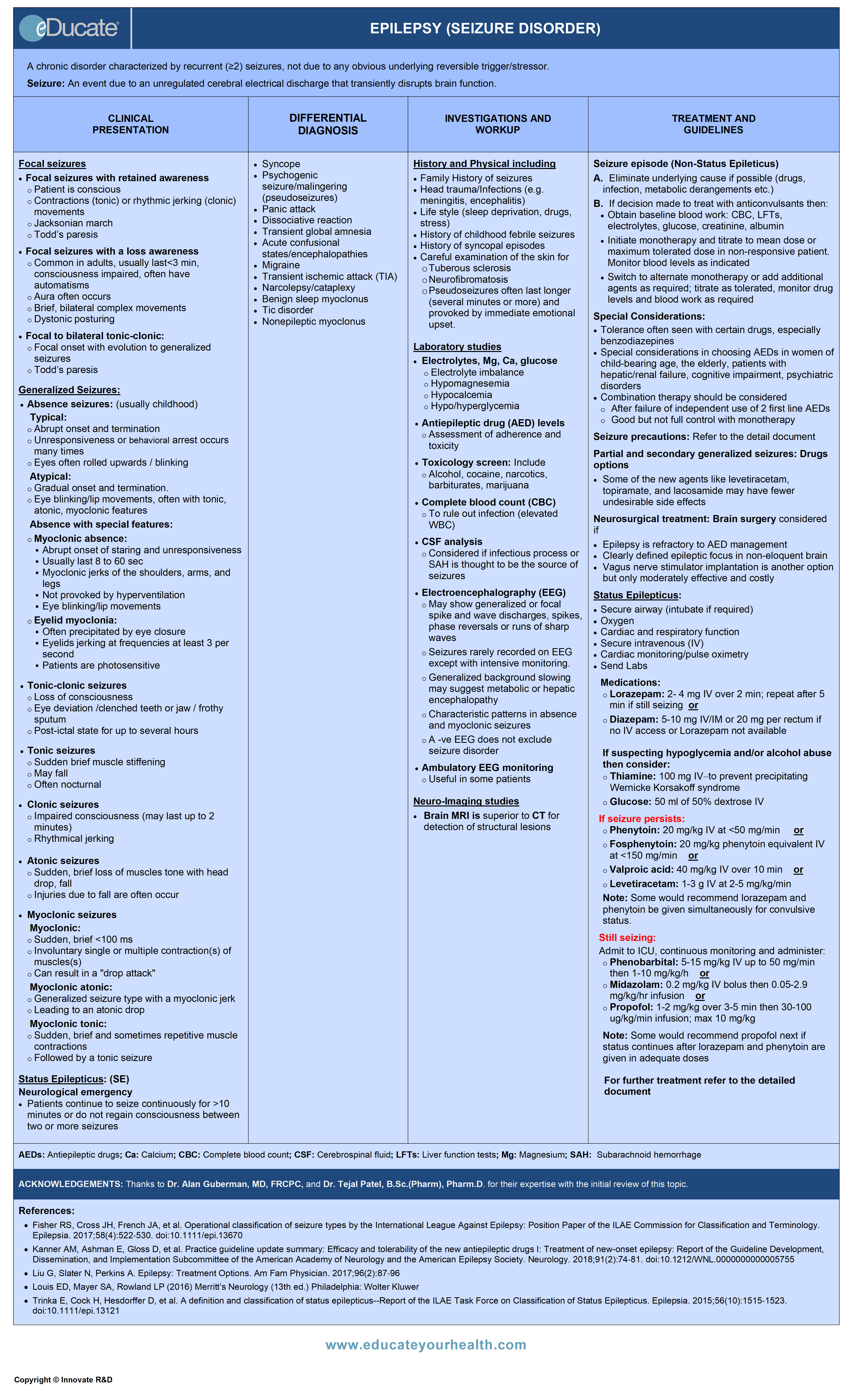

Epilepsy (Seizure Disorder)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

Thanks to Dr. Alan Guberman, MD, FRCPC, Professor of Medicine (Neurology) University of Ottawa, The Ottawa Hospital-Civic Campus, Ottawa, ON Canada, and Dr. Tejal Patel, B.Sc.(Pharm), Pharm.D., Clinical Assistant Professor, School of Pharmacy, University of Waterloo, ON Canada for their expertise with the initial review of this topic.

[pdf-embedder url=”https://www.educateyourhealth.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Epilepsy-Brochure.pdf” width=”750″]

Definition

A chronic disorder characterized by recurrent (≥2) epileptic seizures, not due to any obvious underlying reversible trigger/stressor.

Epileptic Seizure: Paroxysmal event due to an abnormal, unregulated cerebral (neuronal) electrical discharge that transiently disrupts normal brain function.

Classification of Epileptic Seizures:

There are more than 40 types of seizures; most are classified within 2 main categories.

EPILEPSY SYNDROMES

Epilepsy syndromes are disorders in which epilepsy is a main feature and have a relatively consistent seizure type, age of onset, etiology, and prognosis.

Etiology

Epidemiology

– Incidence

- Approximately 0.3-0.5% in different populations worldwide

- Approximately 15,500 new cases per year in Canada

- Approximately 200,000 new cases of epilepsy are diagnosed in the US each year

- Approximately 45,000 new cases in children <15 years old

- Incidence is growing most rapidly in the elderly

– Prevalence

- Approximately 50 million affected worldwide

- Approximately 5-10 persons per 1000

- Approximately 0.6% of the Canadian population

– Gender: Male = Female

– Family history: Increases risk 3-fold

Pathophysiology

Seizure has three phases:

- Initiation

- Propagation

- Termination

1) Initiation phase: Characterized by two simultaneous events:

- High-frequency bursts of action potentials

- Hypersynchronization of a neuronal population

- Bursting activity is caused by:

- Long-lasting depolarization of the neuronal membrane due to influx of extracellular calcium (Ca2+) and sodium (Na+)

- This is followed by a hyperpolarizing afterpotential mediated by:

- Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptors

- Potassium (K+) efflux

- Chloride (Cl–) influx

- Synchronized bursts from a sufficient number of neurons result in a spike discharge on EEG

2) Propagation phase: Characterized by spread of partial seizures within the brain.

3) Termination phase: Not fully understood but may involve restoration of neuronal inhibitory processes and/or “neuronal exhaustion”.

The mechanisms underlying absence seizures involve repetitive oscillations in a circuit between thalamic specific and reticular nuclei and the cerebral cortex. The abnormal neuronal firing in this circuit depends on calcium-T channels which are activated by GABA-mediated membrane hyperpolarization.

Clinical Presentation

Focal seizures:

Focal seizures with retained awareness:

- Patient is conscious

- Contractions (tonic) or rhythmic jerking (clonic) movements

- May involve 1 entire side of body OR

- May be more localized (e.g., hands, feet, face)

- Jacksonian march:

- Sequential spread of seizure activity along a limb or hemibody

(e.g. beginning in hand, progressing up the arm, to face); can be motor or sensory

- Sequential spread of seizure activity along a limb or hemibody

- Todd’s paresis:

- Focal symptoms, usually weakness (but may include speech dysfunction, etc.) for up to several hours post-ictally; reflects the function of the focus of origin of the seizure

Focal seizures with a loss awareness:

Most common epileptic seizures in adults

- Most commonly originate from temporolimbic structures

- Typically last <3 minutes

- Loss of contact with surroundings

- Dystonic posturing

- Brief, bilateral complex movements

- Automatisms (stereotyped, repetitive behaviors, purposeless speech and oral movements such as lip smacking)

- Aura may occur (often very individualized) and may include:

- Dizziness, nausea, “epigastric rising” sensation, deja-vu, olfactory hallucination

Postictal phase, characterized by

- Somnolence/confusion

- ± Headache for up to several hours

- Amnesia for the event

Focal to bilateral tonic-clonic :

- Focal onset (speech, motor, sensory) with evolution into generalized seizures

- Todd’s paresis (described above)

Generalized seizures:

Absence seizures (formerly petit mal)-usually in childhood

- Typical absence seizures

- Abrupt onset and ending

- Unresponsiveness/behavior arrest

- Typically last <10 seconds

- Eye rolling upwards/blinking

- May be precipitated by hyperventilation

- Atypical absence seizures

- Gradual onset and ending

- Slight movements of the lips

- Often with tonic, atonic, myoclonic features

- Not provoked by hyperventilation

- Associated with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome

A childhood epileptic encephalopathy, characterized by: Seizures, mental retardation and abnormal EEG with generalized slow spike-and-wave discharge

- Absence with special features

- Myoclonic absence:

- Usually lasts 8 to 60 sec

- Abrupt onset of staring and unresponsiveness

- Accompanied by myoclonic jerks of the shoulders, arms, and legs with a concomitant tonic contraction

- Rhythmic protrusion of the lips, twitching of the corners of the mouth, or jaw jerking

- Not provoked by hyperventilation

- Eyelid myoclonia: (also known as Jeavons Syndrome)

- May or may not be associated brief loss of awareness

- Often precipitated by eye closure

- Eyelids jerking at frequencies at least 3 per second

- Upward eye deviation

- Patients are photosensitive

Tonic-clonic Seizures (formerly grand mal)

- Loss of consciousness at onset

- Usually, last >30 sec and <5 minutes

- Eye deviation

- Clenched teeth or jaw with cheek, lip or tongue biting

- Frothy sputum

- Labored breathing/cyanosis

- Urinary/fecal incontinence

- Tonic phase (generalized muscle contraction and rigidity)

- Clonic phase (sustained contraction followed by rhythmic contractions of all 4 extremities)

- Postictal phase (confusion, somnolence, fatigue, ± headache)

- Todd’s paresis (as described above), suggests focal seizure onset with secondary generalization

Tonic seizures

- Impaired consciousness

- Sudden brief muscle stiffening

- Jaw clenching

- Brief periods of apnea (last usually <60 sec)

Clonic seizures

- Impaired consciousness(may last up to 2 minutes)

- Confusion

- Rhythmical jerking muscle contractions that usually involve:

- Arms/neck/face/upper body

Atonic seizures (also known as drop seizures)

- Impaired consciousness, usually last <15 seconds

- Sudden, brief loss of muscle tone

- Falls, sometimes with injury are common

Myoclonic seizures

- Myoclonic:

- Sudden, brief <100 ms and sometimes repetitive muscle contractions

- Involuntary single or multiple contraction(s) of muscles(s) or muscle groups

- Can result in a “drop attack”

- Myoclonic atonic:

- Generalized seizure type with a myoclonic jerk

- Leading to an atonic drop

- Myoclonic tonic:

- Sudden, brief and sometimes repetitive muscle contractions

- Followed by a tonic seizure

Status Epilepticus (SE):

Neurological emergency

- Seizures may be generalized convulsive (tonic-clonic or myoclonic seizures), non-convulsive (absence) or partial (focal)

- Generalized tonic-clonic status: Presents as either

- Continuous generalized seizures lasting >10 minutes

- Patients do not fully regain consciousness between ≥2 generalized tonic-clonic seizures

Status epilepticus is a condition resulting either from the failure of the mechanisms responsible for seizure termination or from the initiation of mechanisms that lead to abnormally prolonged seizures (after time point t1). It is a condition that can have long-term consequences (after time point t2), including neuronal death, neuronal injury, and alteration of neuronal networks, depending on the type and duration of seizures.

Time point t1 indicates when treatment should be initiated, and time point t2 indicates when long-term consequences may appear

Differential Diagnosis

SEIZURES

- Syncope

- Psychogenic seizure/malingering (pseudoseizures)

- Panic attack

- Dissociative reaction

- Transient global amnesia

- Acute confusional states/encephalopathies

- Migraine

- Transient ischemic attack (TIA)

- Narcolepsy/cataplexy

- Benign sleep myoclonus

- Tic disorder

- Nonepileptic myoclonus

Investigation and Workup

History and Physical: Detailed description of seizures/ spells including triggering factors

- New onset vs evidence of previous seizure disorder or history of prior seizures, including history of febrile seizures, unexplained nocturnal events, seizures misinterpreted as daydreaming or panic attacks

- History of previous unexplained syncopal episodes

- Family history of seizures

- History of developmental delay-genetic-link or acquired brain injury

- History of head trauma, stroke, intracranial infections (e.g. meningitis/encephalitis)

- Assessment of prescribed medication including interactions which can reduce the efficacy of antiepileptic drugs

- Excess or chronic use of alcohol and/or recreational/illicit drugs

- Medication adherence for those already on anticonvulsants

- Triggering or threshold-lowering factors including sleep deprivation, infections, and emotional upset

- New persistent neurological deficits that might suggest structural brain injury

- Psychogenic causes with or without secondary gain

- Careful examination of the skin for: Harmatomas/facial angiofibromas (tuberous sclerosis) and neurofibromas (neurofibromatosis)

Laboratory Studies

Check for serum glucose, electrolytes, including Ca, Mg, and PO4 to assess for:

- Hypo/hyperglycemia

- Hypo/hypernatremia

- Hypomagnesemia

- Hypocalcemia

- Hypophosphatemia

Antiepileptic drug (AED) levels:

- Assessment of adherence and toxicity

Toxicology screens:

- Include alcohol, cocaine, narcotics, barbiturates, marijuana

Complete blood count (CBC):

Electroencephalography (EEG):

- A negative EEG does not exclude seizure disorder

- Most EEGs are interictal and findings which occur only during seizures may be missed

- Repeated EEGs and sleep deprivation increase the yield

- Even ictal EEGs may be negative with certain focal seizures

Various epileptiform abnormalities can also be seen in patients who have not had seizures. Focal spiking or generalized spike-wave discharges/bursts, however, have a high correlation with epilepsy.

Common EEG findings in epilepsy

Intensive EEG-Video monitoring:

- Used for differentiating non-epileptic from epileptic spells

- Can be done as an out-patient or in-patient

- Used for pre-surgical workup in candidates for epilepsy surgery to identify a focus and the nature of seizures

Ambulatory EEG monitoring:

- May be useful for some patients who are having seizures or spells in particular settings or infrequently

Brain electrical mapping:

- Sometimes done to locate a focal area of brain aberrant activity that has already been suggested on a regular EEG but rarely adds useful information

Imaging Studies

CT / MRI of brain:

- Brain imaging should be considered as part of the neurodiagnostic evaluation of adults presenting with an apparent unprovoked first seizure

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is the preferred neuroimaging method presenting with first afebrile seizure

- Rule-out acute intracranial pathology, such as tumors, hemorrhage, abscess, major developmental disorders, etc. MRI superior in evaluation of the temporal lobes, and particularly helpful for diagnosing subtle cortical dysplasias, migrational abnormalities, mesial temporal sclerosis, small tumors or hamartomatous lesions, cavernous hemangiomas

Treatment

2. New-onset seizure episode (Non-Status Epilepticus)

Note: A single unprovoked seizure is usually not treated unless there is an underlying cerebral lesion or EEG abnormalities such as generalized spike-wave bursts associated with a high likelihood of recurrence, in which case the patient may be treated.

- Eliminate underlying cause if possible (drugs, infection, metabolic derangements etc.)

- If decision made to treat with anticonvulsants then:

- Obtain baseline blood work: CBC, LFTs, electrolytes, glucose, creatinine, albumin

- Initiate monotherapy and titrate to average dose as tolerated

- Obtain blood work for drug levels at steady state and repeat as required

- Switch to alternative monotherapy or add additional agents as required; titrate as tolerated; be aware of potential drug-drug interactions and decreased efficacy; monitor drug levels and blood work as required

- Patients with resistance to monotherapy-consider:

- Diagnostic possibilities other than epilepsy (e.g. pseudoseizures, presyncope/syncope)

- Lifestyle issues aggravating seizures (e.g. poor sleep, drugs, alcohol)

- Assess medication adherence

- Reduced AED efficacy due to drug-drug interaction

- Progressive neurological condition/lesion

- Combination therapy should be considered:

- After failure of independent use of 2 first-line AEDs OR

- The first well-tolerated drug substantially improves seizure control but fails to produce complete seizure control at maximal dosage

- Seizure precautions:

Until condition controlled, patients should be advised to discontinue, restrict or avoid:- Operating heavy machinery/Driving

- Solo use of bathtubs/hot-tubs or swimming alone

- Heights (e.g. ladders; balconies in high rise buildings)

- Potentially dangerous sports such as scuba diving, rock climbing, sky-diving, horseback riding

- Primary and secondarily generalized seizures (drugs options):

- Many AEDs can be effective in both primary and secondarily generalized seizures

- Newer agents like levetiracetam, lamotrigine, and lacosamide may have better tolerability

Neurosurgical treatment (considered if):

- Epilepsy is refractory to AED management

- Clearly defined epileptic focus in non-eloquent brain

[/cq_vc_tab_item][cq_vc_tab_item tabtitle=”Medication Dose”]MEDICATIONS:

Antiepileptic drugs considered in first-line treatment of epilepsy

- Carbamazepine/Carbamazepine-CR

- Oxcarbazepine

- Lamotrigine

- Levetiracetam

- Phenytoin

- Topiramate

- Divalproex sodium or valproic acid

- Ethosuximide (used in absence seizure)

Mechanism

Carbamazepine, Oxcarbazepine, Phenytoin, Lamotrigine

- Blocks sodium channels

Topiramate

- Blocks sodium channels

- Enhances GABA activity

- Decreases glutamate activity by blocking AMPA receptors

- Inhibits carbonic anhydrase

Valproate

- Blocks sodium channels

- Blocks calcium channels

- Enhances GABA activity

Levetiracetam

- Possibly acts by binding to synaptic vesicular protein

Ethosuximide

- The exact mechanism is unknown but suggested to involve reduction of the current in neuronal T-type calcium channels

Dose:

Carbamazepine

- Tablet: 100 mg PO BID for 3-7 days then increase to 200 mg PO BID or TID as tolerated; Maximum dose 1800 mg/day in most patients, can go higher up to 2400 mg/day in patients with inducers

- Suspension: Start with1 teaspoonful (100 mg/5 ml) PO once daily up to usual of 400 mg/day in 3-4 divided doses; increasing by 200 mg/ week in divided doses; Maximum dose 1200 mg/day

Caution: Monitor CBC, LFTs, carbamazepine levels within first 1-2 months of initiation to assess for blood dyscrasias. Neutropenia is often dose-related, and seldom requires discontinuation. However, if lower doses used to avoid neutropenia, efficacy may also be compromised

Note: Drug levels may fall after approximately 3 weeks due to autoinduction of metabolism, therefore steady state levels are only achieved about 3-4 weeks after a steady dose has been established

Lamotrigine: Depends on whether lamotrigine is being used as a monotherapy, or combined with an enzyme inhibitor (cytochrome P450 3A4) such as valproate or an enzyme inducer agent such as carbamazepine, or both.

Dose initiation and maintenance:

- Monotherapy or concomitant use of both enzyme inducer (e.g. carbamazepine) and enzyme inhibitor (e.g. valproate):

- 25 mg PO once daily for 1-2 week; then 25 mg PO BID for 1-2 weeks, then increase every 1-2 weeks by 25-50 mg until at 50-100 mg BID as maintenance

- If used with concomitant CYP450 enzyme inducer alone (e.g. carbamazepine):

- 50 mg PO once daily for 1-2 week; then 50 mg PO BID for 1-2 weeks, then increase every 1-2 weeks by 100 mg until at 150-300 mg BID as maintenance

- If used with concomitant enzyme inhibitor alone (e.g. valproate):

- 25 mg PO every other day for 1-2 week; then 25 mg PO once-a-day for 1-2 weeks, then increase every 1-2 weeks by 25-50 mg until at 50-100 mg BID as maintenance

Levetiracetam

- 250-500mg PO BID; then increase by 250-500 mg every 1-2 weeks; Maximum 4000 mg/day

Oxcarbazepine:

- 300 mg PO BID; usual dose of 1200 mg/day in 2 divided doses. Can be increased by 600 mg/day at weekly intervals; Maximum 2400 mg/day

Phenytoin:

- 300 mg/day PO, (single or divided dose); effective total serum level are 40-80 umol/L (10-20 µg/mL)

- Note:

- Assess for steady state serum levels after 7days and adjust weekly by adjusting daily dose by 50-100 mg increments/decrements

- Serum albumin (normal 35-50 g/L) affects total phenytoin levels and should be assessed at the same time

- Low doses may be required in hypoalbuminemic states

- Corrected phenytoin equation:

Phenytoin loading dose:

- Intravenous: 20 mg/kg (15 mg/kg in the elderly) IV adult single dose or in 2-3 divided doses every 2-4 hrs. Cardiac monitoring usually required if single dose of 1 g is being administered

- Infusion rates: In adults 25-50 mg/min, diluted in 1 liter 0.9% NaCl

- Oral load (not for status epilepticus): 300-400 mg PO BID for 2 days

- Maintenance dose: 200 to 300 mg PO or IV once-a-day, may be used initially and adjust in 50-100 mg/day increments every 2-7 days, depending on clinical response and serum levels

Topiramate:

- Initial dose 25mg PO BID for the first week; increase by 25 mg PO BID every week to 50 mg BID. May continue to increase further by 25-50 mg weekly until at 200-400 mg PO daily

- Monotherapy is 200-400 mg PO daily given BID in children >10 yrs and adults in partial seizures

Valproic acid/Divalproex sodium:

- Initial 10-15 mg/kg/day, increase by 5-10 mg/kg/week; Adults dosing 250 mg BID for 3 days, then increase to TID for 3 days.

May further titrate to 500 mg BID or TID if needed; Maximum dose: 60 mg/kg/day - Note: Monitor plasma trough levels to determine therapeutic levels (50-150 mg/ml or 350-700 μmol/L)

Ethosuximide:

- Initial 500 mg/day PO in single or divided dose; Slowly increase dose by 250 mg/day after every 4-7 days until seizures are controlled; Maximum dose 1.5 g/day, if it exceeds 1.5 mg/day clinician should monitor very closely

Agents that are more often used in combination therapy are:

- Brivaracetam

- Clobazam

- Clonazepam

- Eslicarbazepine

- Felbamate

- Gabapentin

- Lacosamide

- Perampanel

- Primidone

- Rufinamide

- Tiagabine

- Vigabatrin

- Zonisamide

Potential Mechanism(s):

Brivaracetam:

- Exact mechanism of action is unknown

- Displays a high and selective affinity for synaptic vesicle protein 2A (SV2A) in the brain, which may contribute to the anticonvulsant effect

Clobazam/Clonazepam:

- Benzodiazepines binding to GABA receptor, increases permeability to chloride ions-results in membrane stabilization

Eslicarbazepine:

- Exact mechanism of action is unknown

- It is thought to involve inhibition of voltage-gated sodium channels

Felbamate:

- Mechanism of action is unknown but has properties in common with other marketed anticonvulsants; has weak inhibitory effects on GABA-receptor binding, benzodiazepine receptor binding, and is devoid of activity at the MK-801 receptor binding site of the NMDA receptor-ionophore complex

Gabapentin:

- Binds to voltage-gated calcium channels specifically possessing the alpha-2-delta-1 subunit located presynaptically and may modulate release of excitatory neurotransmitters

Lacosamide:

- Enhances slow inactivation of sodium channels

Perampanel:

- Selective, non-competitive antagonist of the ionotropic α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) glutamate receptor on post-synaptic neurons

Primidone / Tiagabine:

- Enhances GABA activity. Phenobarbital and primidone (metabolized partially to Phenobarbital) also block sodium channels

Vigabatrin:

- Irreversibly inhibits GABA-T, increasing GABA levels within the brain

Zonisamide:

- May stabilize neuronal membranes and suppress neuronal hypersynchronization through action at sodium and calcium channels. Does not affect GABA activity

Dose:

Brivaracetam:

- Initial 50 mg PO/IV BID; Max. 100 mg PO/IV BID

- Hepatic Impairment: Initial 25 mg PO/IV BID; Max. 75 mg PO/IV BID

Clobazam:

- Initial starting dose 5-10 mg PO at bedtime; maintenance from 10-80 mg/day PO at bedtime; usual dose 10-20 mg/day PO at bedtime; Maximum 80 mg/day in 2 divided doses (1/3 a.m. and 2/3 at bedtime)

Clonazepam:

- Initial starting 1.5 mg/daily PO in 3 divided doses; may increase 0.5-1 mg every 3rd day until seizures are controlled; Max. 20 mg/daily in divided doses

Eslicarbazepine:

- Initial 400 mg PO once daily; maintenance dose 800 mg once daily adjust after one or two weeks; max. 1200 mg once daily

- Renal Impairment (CrCl <50 mL/min): Initial 200 mg PO once daily; maintenance dose 400 mg once daily adjust after two weeks; Max. 600 mg once daily

Felbamate:

- 1,200 mg/d in 3-4 divided doses; Maximum 3,600 mg/d

Gabapentin:

- Initial 100-300 mg PO TID; Usual dose is 900-1800 mg/day in 3 divided doses; Maximum 2400 mg/day are well tolerated

- Note: Doses are to be adjusted according to the ClCr

Perampanel:

- In the presence of enzyme-inducing AEDs: Initial 2 mg PO once daily; May be increased in 2 mg at weekly intervals as tolerated; Max. 12 mg PO once daily

- In the absence of enzyme-inducing AEDs: Initial 2 mg PO once daily; May be increased in 2 mg at 2-week intervals as tolerated; Max. 12 mg PO once daily

Primidone:

- Start 100-125 mg PO at bedtime for 3 days; continue with the same dose by increases frequency from Day 4-6 BID and Day 7-9 TID; Maintaining 250 mg/dose BID or TID, from Day 10 onwards; Maximum dose 2 gm/day

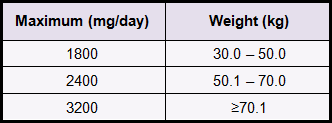

Rufinamide:

- In adults and children ≥30 kg: 200 mg PO BID may be increased every two weeks intervals by 5 mg/kg/day as tolerated

Tiagabine:

Tiagabine:

- 4 mg PO daily; adjust weekly to maximum 56 mg PO in 2-4 divided doses

Vigabatrin:

- Initial 500 mg PO BID; may be increased in 500 mg at weekly intervals; Maximum 1.5 gm PO BID

Zonisamide:

- Start 100 mg/day; may increase dose by 100 mg/day after at least every 2 weeks; Maximum 400 mg/day

Lacosamide:

- 50 mg BID; may be increased at weekly intervals by 100 mg/day; usual 200-400 mg/day

Agents that are commonly used in status epilepticus:

- Benzodiazepines

- Hydantoin

- Barbiturates

- General anesthetic

- Electrolyte supplement included in the anticonvulsant category

- Diazepam

- Lorazepam

- Midazolam

Mechanism:

- Benzodiazepines bind to the gamma sub-unit of the GABA receptor and enhance the inhibitory effect of GABA

- Increase the frequency of channel opening events, leads to increase in chloride ion conductance and inhibition of the action potential

- All benzodiazepines exert five major effects: (i) Anxiolytic (ii) Hypnotic (iii) Muscle relaxant (iv) Anticonvulsant (v) Amnesic (impairment of memory)

Dose:

Diazepam:

- IV: May be used for seizure status; 5-10 mg IV push (every 5-10 min) prn seizure to maximum of 30-40 mg

- Note: Monitor for respiratory depression at higher doses. May require intubation

- Rectal gel: Initial dose 0.2 mg/kg

Lorazepam:

- May be used for seizure status: 1-2 mg IV push every 5-10 min prn; Maximum of 6-8 mg

- Note: Monitor for respiratory depression at higher doses. May require intubation

Midazolam:

- 2.5 mg IV over 2 minutes. May be used for seizure status

- Note: Monitor for respiratory depression at higher doses. May require intubation

- Phenytoin

- Fosphenytoin

Mechanism:

After administration, plasma esterases convert fosphenytoin to phosphate, formaldehyde, and phenytoin as the active moiety.

- Inhibits calcium flux across neuronal membranes

- Blocks sodium channels

Dose:

Phenytoin: Status epilepticus

- Adults: 15-20 mg/kg IV administered at a rate of 25-50 mg/minute. If seizures are not controlled, additional doses of 5-10 mg/kg IV (maximum 30 mg/kg) may be given

Fosphenytoin:

- Status epilepticus: Loading dose 15-20 mg PE/kg IV administered at 100-150 mg PE/minute

- Nonemergent loading and maintenance dosing (IV or IM): Loading dose 10-20 mg PE/kg (IV rate: Infuse over 30 minutes; maximum rate: 150 mg PE/minute). Initial daily maintenance dose: 4-6 mg PE/kg/day

Note: Infusion rates for fosphenytoin are expressed as phenytoin sodium equivalent (PE).

- Phenobarbital

- Thiopental

- Pentobarbital

Mechanism:

- Acts on GABA-A receptors, enhances the synaptic action of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)

- Also, inhibit sodium and calcium channels

Dose:

Phenobarbital (status epilepticus):

- Loading dose: 10-20 mg/kg IV (maximum rate ≤60 mg/minute in patients ≥60 kg); may repeat dose in 20-minute intervals; Maximum dose: 30 mg/kg

- Maintenance: 1-3 mg/kg/day IV in divided doses; 50-100 mg PO 2-3 times/day

- Note: Monitor for respiratory depression at higher doses. May requires intubation

Thiopental:

- Seizures: 75-250 mg/dose IV; repeat as needed, administer slowly over 20-30mins

Pentobarbital:

Refractory Status Epilepticus (IV):

- Loading dose: 5-15 mg/kg IV administered slowly over 1 hour. Begin in lower dose range in hypotensive patients. Maintenance infusion 0.5-1 mg/kg/hr titrated up to 10 mg/kg/hour as required to maintain burst suppression on EEG

- Note: Adjust dose based on hemodynamics, seizure activity, and EEG

- Propofol

Mechanism:

- Short-acting intravenous general anesthetic, with several mechanisms

- It causes CNS depression through GABAA receptors by its agonist action

- It also decreases glutamatergic activity

Dose:

Propofol (increasingly used in status epilepticus not responding to initial therapy in ED)

- 2-10 mg/kg/hr IV titrate to desired effect

- More than 5 mg/kg/hour IV or if used >48 hrs, increases the risk of hypotension, consider alternative treatment to avoid the risk associated with long-term infusion

- Magnesium sulfate (MgSO4)

- Used mainly in seizures due to severe hypomagnesemia or eclampsia

Mechanism:

- Essential for the activity of many enzymatic reactions and plays an important role in neurotransmission and muscular excitability

- Prevents or controls convulsions by blocking neuromuscular transmission and decreasing the amount of acetylcholine liberated at the end plate by the motor nerve impulse

- Other effects are promoting bowel evacuation, slowing heart rate/conduction, smooth muscle relaxation, vasodilation

Dose:

Hypomagnesemia:

- Magnesium sulfate 2 g IV over 10 minutes; calcium administration may also be appropriate as many patients are also hypocalcemic

Eclampsia:

- Maximal rate of infusion 2 g/hour IV to avoid hypotension; doses of 4 g/hour have been employed in emergencies; optimally, should add magnesium to IV fluids, but bolus doses are also effective

[/cq_vc_tab_item][/cq_vc_tabs]

Clinical Trials

- Ethosuximide, Valproic Acid, and Lamotrigine in Childhood Absence Epilepsy

- Comparison of levetiracetam and controlled-release carbamazepine in newly diagnosed epilepsy

- Comparison between lamotrigine and carbamazepine in elderly patients with newly diagnosed epilepsy

- A randomized study of gabapentin, lamotrigine, and carbamazepine

- The SANAD study of effectiveness of carbamazepine, gabapentin, lamotrigine, oxcarbazepine, or topiramate for treatment of partial epilepsy

- The SANAD study of effectiveness of valproate, lamotrigine, or topiramate for generalized and unclassifiable epilepsy

- The Teratogenicity of Anticonvulsant Drugs

- Final results from 18 years of the International Lamotrigine Pregnancy Registry

- Effectiveness of first antiepileptic drug

- A Randomized, Controlled Trial of Surgery for Temporal-Lobe Epilepsy drug

- Rufinamide for generalized seizures associated with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome

- Efficacy and safety of oral lacosamide as adjunctive therapy in adults with partial-onset seizures

- Efficacy and safety of adjunctive ezogabine (retigabine) in refractory partial epilepsy

Physician Resources

Tips for Patient Care:

- Encourage patient to identify and avoid triggers

- Lifestyle modifications especially for those with frequent, uncontrolled seizures:

- Avoid sleep deprivation

- Avoid alcohol and recreational drugs

- Excessive use of video games may trigger seizures

- Medication adherence

- Reduce stress

Patient safety:

- Inform Transport Ministry-Re: Patient to avoid driving until symptoms have been brought under control

- Patient advised to avoid:

- Operating/using heavy machinery, power tools

- Driving

- Solo use of bathtubs/hot-tubs (showers preferable)

- Swimming alone

- Heights (e.g. ladders; roofs, balconies in high rise buildings)

- Cooking on exposed flames (microwave ovens preferred)

- Front burners on stove (rear burners preferred)

- Certain sports: rock-climbing, hang-gliding, scuba diving, downhill skiing, horseback riding

- Recommend a medic-alert bracelet/necklace

Advice for family members (during seizure attack):

- Place patient on the side and clear away any objects that may cause physical harm

- Do not place patient in restraints

- Protect patient’s head

- Avoid placing fingers or other objects (spoons) into the patient’s mouth

- With patient on his/her side excess saliva should flow out of the mouth

- Wipe away excess saliva

- Call Emergency medical services (911) for assistance

- Assess potential injuries sustained during a generalized tonic-clonic seizure

- Wounds or fractures can occur and urgent medical treatment may be required

Medications:

- Evaluate cost, affordability and insurance coverage for patients

- Whenever possible simplify medication regimens

- If possible, use monotherapy, and monitor serum levels of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) as indicated

- Monitor all patients on AED therapy for notable behavior changes, e.g. suicidal thoughts, depression

- Consider concurrent risk factors and disease states when prescribing

- Discuss potential adverse events/side effects of medications.

- Counsel women of childbearing age regarding potential teratogenicity of AEDs

Social and stress factors:

- Patient & family members should be well informed about the type of epilepsy, triggers, treatment, safety measures and what should be done for an attack

- Certain types of childhood epilepsy improve with age while others may not

- Include family or social support in lifestyle modification

2. Scales and Tables:

References

Core Resources:

- Brust JCM (2007) Current Diagnosis and Treatment (Neurology) (2nd ed.) New York: McGraw Hill

- Compendium of Pharmaceuticals and Specialties (CPS). Canadian Pharmacist Association. Toronto: Webcom Inc. 2012

- Day RA, Paul P, Williams B, et al (eds). Brunner & Suddarth’s Textbook of Canadian Medical-Surgical Nursing. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2010

- Fisher RS, Cross JH, French JA, et al. Operational classification of seizure types by the International League Against Epilepsy: Position Paper of the ILAE Commission for Classification and Terminology. Epilepsia. 2017;58(4):522‐530. doi:10.1111/epi.13670

- Foster C, Mistry NF, Peddi PF, Sharma S, eds. The Washington Manual of Medical Therapeutics. 33rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010

- Gray J, ed. Therapeutic Choices. Canadian Pharmacists Association. 6th ed. Toronto: Webcom Inc. 2011

- Kanner AM, Ashman E, Gloss D, et al. Practice guideline update summary: Efficacy and tolerability of the new antiepileptic drugs I: Treatment of new-onset epilepsy: Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Epilepsy Society. Neurology. 2018;91(2):74‐81. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000005755

- Katzung BG, Masters SB, Trevor AJ, eds. Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. 11th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2009

- Liu G, Slater N, Perkins A. Epilepsy: Treatment Options. Am Fam Physician. 2017;96(2):87‐96

- Longo D, Fauci A, Kasper D, et al (eds). Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 18thed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2011

- Louis ED, Mayer SA, Rowland LP (2016) Merritt’s Neurology (13th ed.) Philadelphia: Wolter Kluwer

- McPhee SJ, Papadakis MA, eds. Current Medical Diagnosis & Treatment. 49th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2010

- Pagana KD, Pagana TJ eds. Mosby’s Diagnostic and Laboratory Test Reference. 9th ed. St. Louis: Elsevier-Mosby; 2009

- Rowland LP et al. (2010) Merritt’s Neurology (9th ed.) Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins

- Scheffer IE, French J, Hirsch E, et al. Classification of the epilepsies: New concepts for discussion and debate-Special report of the ILAE Classification Task Force of the Commission for Classification and Terminology. Epilepsia Open. 2016;1(1-2):37‐44. Published 2016 Jul 21. doi:10.1002/epi4.5

- Skidmore-Roth L. ed. Mosby’s drug guide for nurses. 9th ed. St. Louis: Elsevier-Mosby; 2011

- Skidmore-Roth L, ed. Mosby’s nursing drug reference. 24th ed. St. Louis: Elsevier-Mosby; 2011

- Trinka E, Cock H, Hesdorffer D, et al. A definition and classification of status epilepticus–Report of the ILAE Task Force on Classification of Status Epilepticus. Epilepsia. 2015;56(10):1515‐1523. doi:10.1111/epi.13121

Online Pharmacological Resources:

- e-therapeutics

- Lexicomp

- RxList

- Epocrates Online

Journals/Clinical Trials:

- Ben-Menachem E, Biton V, Jatuzis D, et al. Efficacy and safety of oral lacosamide as adjunctive therapy in adults with partial-onset seizures. Epilepsia, 2007;48:1308-17

- Brodie M.J., Perucca E., Rylin P., et al, for the Levetiracetam Monotherapy Study Group. Comparison of Levetiracetam and controlled-release Carbamazepine in newly diagnosed epilepsy. Neurology, 2007;68:402-408

- Brodie M.J., Overstall P.W., Giorgi L. and The UK Lamotrigine Elderly Study Group. Comparison between lamotrigine and carbamazepine in elderly patients with newly diagnosed epilepsy. Epilepsy Res., 1999;37:81-7

- Cunnington MC, Weil JG, Messenheimer JA et al. Final results from 18 years of the International Lamotrigine Pregnancy Registry. Neurology, 2011;76:1817-23

- Chung S, Ben-Menachem E, Sperling MR et al. Examining the Clinical Utility of Lacosamide: Pooled analyses of three Phase II/III clinical trials. CNS Drugs, 2010;24:1041-1054

- Elger C, Halász P, Maia J, et al; BIA-2093-301 Investigators Study Group. Efficacy and safety of eslicarbazepine acetate as adjunctive treatment in adults with refractory partial-onset seizures. Epilepsia, 2009;50:454-63

- French JA, Costantini C, Brodsky A, von Rosenstiel P; N01193 Study Group. Adjunctive brivaracetam for refractory partial-onset seizures: a randomized, controlled trial. Neurology, 2010;75:519-25

- Glauser T.A., Cnaan A., Shinnar S. et al, for the Childhood Absence Epilepsy Study Group. Ethosuximide, Valproic Acid, and Lamotrigine in Childhood Absence Epilepsy. N Engl J Med, 2010; 362:790-799

- Glauser T, Kluger G, Sachdeo R et al. Rufinamide for generalized seizures associated with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. Neurology, 2008;70:1950-8

- Holmes LB, M.D., Harvey EA, Coull BA et al. The Teratogenicity of Anticonvulsant Drugs. N Engl J Med, 2001;344:1132-8

- Kwan P, Brodie MJ, et al. Effectiveness of first antiepileptic drug. Epilepsia, 2001;42:1255-60

- Marson AG, Al-Kharusi AM, Alwaidh M et al. on behalf of the SANAD Study group. The SANAD study of effectiveness of carbamazepine, gabapentin, lamotrigine, oxcarbazepine, or topiramate for treatment of partial epilepsy. The Lancet, 2007;369:1000-1015

- Marson AG, Al-Kharusi AM, Alwaidh M et al. on behalf of the SANAD Study group. The SANAD study of effectiveness of valproate, lamotrigine, or topiramate for generalized and unclassifiable epilepsy. The Lancet, 2007;369:1016-1026

- M.J. Brodie, MD, H. Lerche, MD, A. Gil-Nagel, MD, and On behalf of the RESTORE 2 Study Group. Efficacy and safety of adjunctive ezogabine (retigabine) in refractory partial epilepsy. Neurology, 2010;75:1817-1824

- Rowan A.J., Ramsay T.E., Collins J.F., et al and the VA Cooperative Study 428 Group. A randomized study of gabapentin, lamotrigine, and carbamazepine. N Engl J Med, 2010;362:790-799

- Wiebe S, Blume W, Girvin JP, et al, for the Effectiveness and Efficiency of Surgery for Temporal Lobe Epilepsy Study Group. A Randomized, Controlled Trial of Surgery for Temporal-Lobe Epilepsy drug. N Engl J Med, 2001;345:311-318