Osteoporosis (OP)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

Thanks to Dr. Philip A. Baer, MDCM, FRCPC, FACR, Internal medicine (Rheumatology), Chair, OMA Section on Rheumatology, VP, Ontario Rheumatology Association, ON Canada, and Dr. Jane Richardson, BSP, PhD, FCSHP, Coordinator – Clinical Pharmacy Services, Saskatoon Health Region, Saskatoon, SK Canada for their expertise with the initial review of this topic.

Definition

Progressive skeletal disorder characterized by low bone mass, deterioration of bone tissue and disruption of bone architecture leading to compromised bone strength and increase in the risk of fractures.

Etiology

Primary osteoporosis:

- Accounts for 80-95% of cases

- Not associated with systemic disorders (related to postmenopausal state or age)

- Age-related – usually starts ≥50 years

- Postmenopausal women

- Men

- Accounts for <5% of cases

- Secondary to any systemic disease (chronic diseases, drug therapy, or lifestyle)

- Can start at any age

Idiopathic osteoporosis:

- Usually young person with fragile bones without any associated disorders

- Hormone and vitamin levels are normal with no obvious reason to have weak bones

- Potential causes:

- Abnormalities of osteoblast function

- Decreased insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1)

- Subclinical estrogen deficiency

- Increased bone turnover

- Juvenile osteoporosis

Risk factors

- Risk factors are additive, i.e. the more risk factors present, the greater the increase in the risk of developing osteoporosis

- Risk factors are identified within indications for bone mineral density

Epidemiology

- Estimated to affect >200 million people worldwide; including ~1.4 million Canadians and >10 million Americans

- Most are postmenopausal women and the elderly

- Affects 1 in 4 women and >1 in 8 men over the age of 50 years

- Over 80% of all fractures in people 50+ are caused by osteoporosis

- Major cause of fractures and fall-related hospital admissions in Canada

Predominant age:

- Primary osteoporosis: 50-70 years

- Age-related osteoporosis: >70 years

- Secondary osteoporosis: Any age

Predominant sex:

- Female > Male

Prevalence: Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study (CaMos) estimates

- Increase as the population ages

- 21.3% in women >50 years

- 5.5% in men >50 years

Mortality/Morbidity:

Hip and vertebral fractures, in particular, are associated with increased morbidity and mortality.

Hip fracture:

- 28% of women and 37% of men who suffer a hip fracture will die within the following year

- The risk of recurrent fracture in the year following a hip fracture is 5-10%

- Nearly 75% of all hip fractures occur in women

- Approximately 44% of hospital discharges after a hip fracture return home; the others are sent to rehabilitation, long-term care facilities, or other hospitals for continuing care (i.e. loss of independence)

Vertebral fracture:

- Patients are at highest risk for subsequent fracture in the first few months following a vertebral fracture

- 20% chance of a repeat vertebral fracture within 1 year of developing a vertebral fracture

- 50-66% of vertebral fractures are not clinically recognized at the time of the fracture

Pathophysiology

- Summary of factors that affect bone metabolism and their possible pathogenic roles:

- Genetic determinants account for 40-80% of the variability in peak bone mass

- Growth hormone or IGF-1 deficiency, as well as receptor defects, result in dwarfism and diminished bone mass

- Glucocorticoids reduce bone formation and increase bone resorption. The decline in the bone formation may be mediated by

- Direct inhibitory effect on osteoblasts

- Inhibition of the production of insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) and testosterone

- Increase in osteoblast and osteocyte apoptosis

- Decrease in intestinal calcium absorption and increase in renal calcium excretion

- Estrogen deficiency has a central role in postmenopausal osteoporosis

- Bone cells and growth plate cartilage contain both the alpha and beta isoforms of the estrogen receptor

- Estrogen inhibits bone resorption

- Men with aromatase deficiency have delayed epiphyseal closure and osteoporosis

- Estrogen decreases osteoclastogenesis

- Estrogen decreases the depth of the erosion cavity caused by the osteoclast

- Estrogen promotes apoptosis of osteoclasts

- Estrogen increases the release of transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta

- Estrogen inhibits the release of TNF-a from T cells which causes osteoclast recruitment

- Estrogen reduces the release of RANK-Ligand (RANK-L) from osteoblasts. RANK-L is a growth factor for osteoclasts

- Imbalance between bone resorption and formation results in bone loss

- Increases in the function and life span of bone-resorbing cells (osteoclasts) and/or inadequate bone formation (reduction in osteoblast number/function) can lead to a greater number of remodeling sites or deeper resorption sites that cannot be adequately filled by osteoblasts

- Bone turnover releases a number of biochemical markers categorized as markers of bone formation or bone resorption as a consequence of the physiological action of osteoblasts and osteoclasts. These turnover markers can be measured in the serum and urine

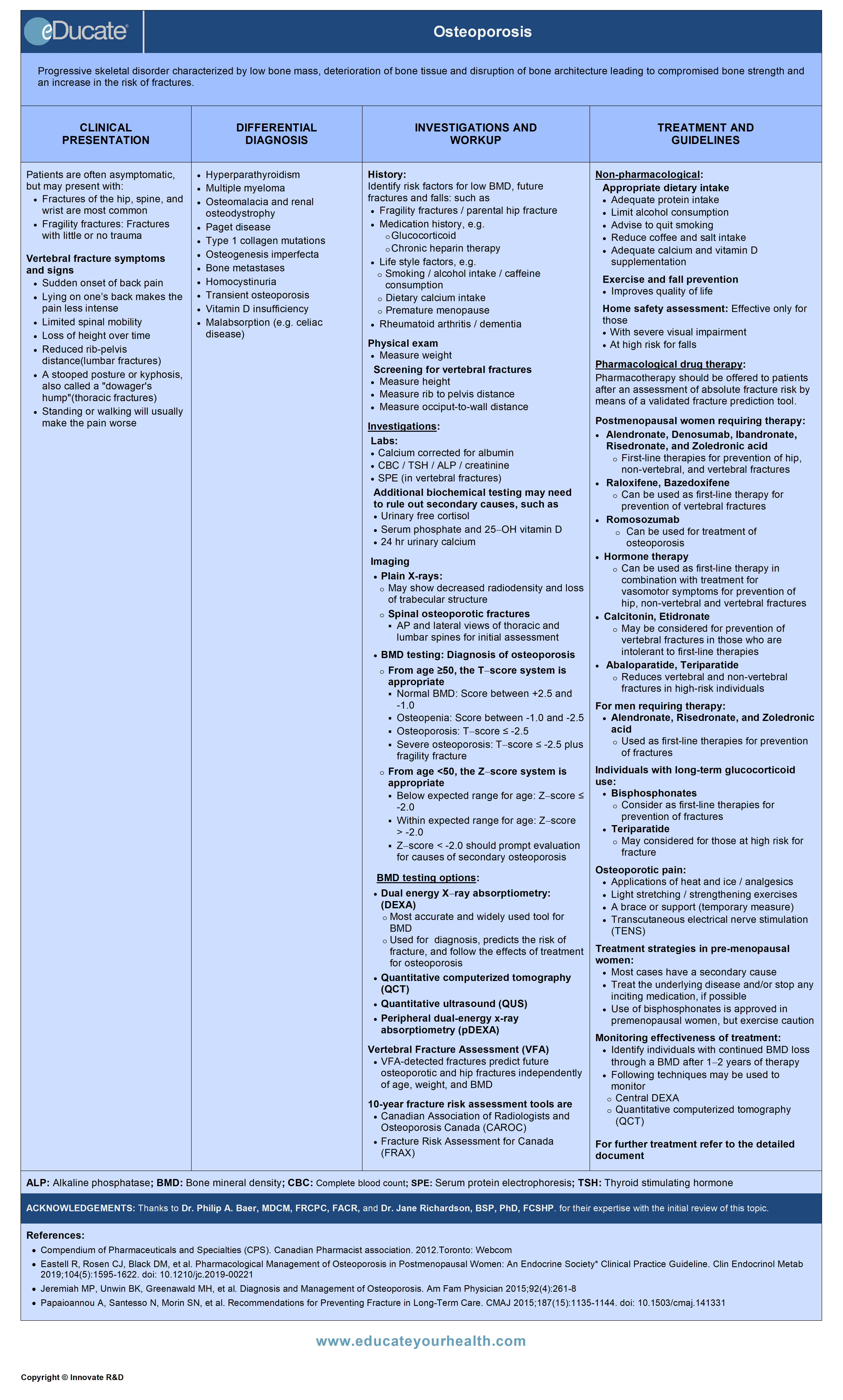

Clinical Presentation

- Usually asymptomatic until fracture occurs

- Fractures of the hip, spine, and wrist are most common

- Fragility fractures: Fractures with little or no trauma, such as fall from sitting or standing height, of a low couch or sofa, or fall down 1-3 steps

- Chronic pain is the common post-fracture symptom, especially after vertebral fracture

- Vertebral fracture symptoms

- Sudden onset of back pain

- Lying on one’s back makes the pain less intense

- Limited spinal mobility

- Loss of height over time

- Reduced rib-pelvis distance

- A stooped posture or kyphosis, also called a “dowager’s hump”

- Standing or walking will usually make the pain worse

- Key risk factors for fall

Differential Diagnosis

- Hyperparathyroidism

- Multiple myeloma

- Osteomalacia and renal osteodystrophy

- Paget disease

- Type 1 collagen mutations

- Osteogenesis imperfecta

- Bone metastases

- Homocystinuria

- Transient osteoporosis

- Vitamin D insufficiency

- Malabsorption (e.g. celiac disease)

Investigation and Workup

- Osteoporosis Canada recommends that all postmenopausal women and men older than 50 years be assessed for the presence of risks factors for osteoporosis

- Postmenopausal women over age 50 years and men who have risk factors for osteoporosis and fracture based on targeted history and physical examination, or those 65 years and older, should undergo screening with DEXA (dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry)

- There are two stages of assessment in identifying high-risk individuals for osteoporosis:

- Risk factors identifying those who should be assessed with a Bone Mineral Density (BMD) test

- Risk factors identifying those at risk of osteoporotic (fragility) fracture who should be considered for therapy

History

Identify risk factors for low BMD, future fractures, and falls:

- Prior fragility fractures after age 40 years

- Family history of osteoporotic fracture/ parental hip fracture

- Medication history

- Such as: glucocorticoid use greater than 3 months in the prior year at a prednisone-equivalent dose of ≥7.5 mg daily

- Chronic heparin therapy

- Lifestyle factors

- Current smoking

- High alcohol intake (≥3 units per day)

- High caffeine consumption

- Dietary calcium intake

- Physical activity

- Weight loss greater than 10% of weight at age 25

- Poor nutrition

- Premature menopause

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Inquire about falls in the previous 12 months and inquire about gait and balance

- Accurate height and weight measurement

- Get-Up-and-Go Test

- Inability to rise from a chair without using the arms and walk a few steps and return

- Dementia

Physical exam:

- Measure Weight

- Weight loss of >10% since age 25 is significant

Screening for vertebral fractures:

- Measure Height

- Measurement of height loss is a good clinical indicator of vertebral fracture

- Historical height loss >6 cm (difference between the tallest recalled height and current measured height) OR

- Prospective height loss of 2 cm (from two or more office visits within 3 years)

- Measure rib to pelvis distance

- ≤2 fingers’ breadth in vertebral fractures

- Measure occiput-to-wall distance and kyphosis

- Measure the distance between the wall and the patient’s occiput as the individual stands straight with heels and back against the wall. Vertebral fractures should be suspected if the distance between the wall and the occiput >5 cm

Laboratory:

For all patients with osteoporosis:

- Calcium corrected for albumin

- Complete blood count (CBC)

- Creatinine

- Alkaline phosphatase

- Thyroid-stimulating hormone

- Serum protein electrophoresis (for patients with vertebral fractures)

- 25-Hydroxyvitamin D* – measure in patients with:

- Recurrent fractures

- Bone loss despite osteoporosis treatment

- Co-morbid conditions that affect vitamin D absorption or action

- *Should be re-measured after three to four months of adequate supplementation and should not be repeated if an optimal level (at least 75 nmol/L) is achieved.

In selected patients based on clinical assessment, additional biochemical testing may be required to rule out secondary causes of osteoporosis, such as:

- Serum testosterone

- Urinary free cortisol

- Vitamin B12 level and intrinsic factor antibody

- Antigliadin and anti-endomysial antibodies

- Serum phosphate

- 24-hour urinary calcium

Imaging:

Plain X-rays:

- Simple x-rays of bones are not very accurate in predicting whether someone is likely to have osteoporosis

- May show decreased radiodensity and loss of trabecular structure

Spinal osteoporotic fractures

- Initial assessment is done with antero-posterior (AP) and lateral views of both the thoracic and lumbar spines

- The standard follow-up only consists of single lateral views of the thoracic and lumbar spine that include T4 to L4 vertebrae

Bone mineral density testing:

- Expressed in terms of T-scores and Z-scores

- Based upon the lowest value for lumbar spine (minimum two vertebral levels), total hip, and femoral neck. If either the lumbar spine or hip is invalid, then the forearm should be scanned and the distal 1/3 region reported

- Diagnosis of osteoporosis is derived from the following classification of BMD measures by a WHO Working Group, based on fracture risk:

- From age 50 years or over, the T-score system is appropriate. ” T-score” is the number of standard deviations (SD) the patient’s BMD is above or below the mean value for that of young-adult reference population

- Normal BMD: T-score between +2.5 and -1.0, inclusive (2.5 SDs above and 1.0 SD below the young adult mean)

- Osteopenia (low BMD): T-score between -1.0 and -2.5

- Osteoporosis: T-score ≤ -2.5

- Severe osteoporosis: T-score ≤ -2.5 plus fragility fracture

- Prior to age 50 years, the age- and sex-matched Z scores are preferred. It is the number of standard deviations below the mean for an age-matched population

- Below expected range for age: Z-score ≤ -2.0

- Within expected range for age: Z-score > -2.0

- Z-score <-2.0 should prompt evaluation for causes of secondary osteoporosis

- Indications for bone mineral density (BMD) testing:

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry:

- Measures bone mineral content and bone area

- Currently, DEXA remains the most accurate and widely used tool for BMD measurement of the central skeleton in the clinical setting

- It is used for diagnosis, predicting the relative risk of fracture, and following the effects of treatment for osteoporosis

- Most often performed on the lower spine and hips

- Therapeutic progress using central DEXA should be monitored in clinical settings one or two years after initiating therapy

- Depending on the clinical situation, central DEXA scans (lumbar spine and hip) may be repeated in 1 to 3 years, on the same instrument, using the same procedure

Quantitative computerized tomography (QCT):

- Quantitative computed tomography (QCT) can be used to assess BMD

- Measures volumetric bone density of the spine and hip and can analyze cortical and trabecular bone separately

- In postmenopausal women, QCT measurement of spine trabecular BMD can predict vertebral fractures, whereas pQCT of the forearm at the ultra-distal radius predicts hip but not spine fractures

- There is lack of sufficient evidence for fracture prediction in men

Quantitative ultrasound (QUS):

- Radiation-free technique used to examine bone in the calcaneus (heel), tibia, patella, and other peripheral skeletal sites for two values:

- The speed of sound in bone (SOS)

- Broadband ultrasound attenuation (BUA)

- Both the SOS and BUA are higher in healthy bone than in osteoporotic bone

- Validated heel QUS devices predict fractures in

- Postmenopausal women (vertebral, hip and overall fracture risk)

- Men 65 years and older (hip and non-vertebral fractures)

Peripheral measurements:

These technologies can only be used to predict fractures. Often measure BMD at several skeletal sites, such as radius, phalanx, calcaneus, tibia, metatarsal.

Ultrasound

- Uses sound waves to measure density at the heel, shin bone, and kneecap

Peripheral dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (pDEXA)

- This test is a modification of the DEXA technique that measures bone density of limbs like the wrist, heel, or finger

- pDEXA is not appropriate for monitoring BMD after treatment

Single-energy X-ray absorptiometry (SXA)

- Measures the wrist or heel

Dual photon absorptiometry (DPA)

- This test usually has a slower scan time than the other methods but it can measure bone density in the spine, hip, or total body

Single photon absorptiometry (SPA)

- Measures bone density in the wrist

X-ray absorptiometry

- Uses an X-ray of the hand and a small metal wedge to calculate bone density

Peripheral quantitative computed tomography (pQCT)

- A higher radiation method of measuring bone density from bones in limbs, such as the wrist

- Predicts hip, but not vertebral fractures

Vertebral Fracture Assessment (VFA):

- VFA-detected fractures predict future osteoporotic and hip fractures independently of age, weight, and BMD

- It is used for further risk stratification and to aid in clinical decision-making regarding pharmacologic interventions

- It will identify moderate (>25% compression) or severe (>40%) vertebral deformities.

- Unequivocal vertebral fractures (>25% height loss with end-plate disruption) unrelated to trauma are associated with a 5-fold increased risk for recurrent vertebral fractures.

- The advantages of VFA versus standard spine x-rays are convenience, lower cost, and markedly lower radiation exposure

Bone turnover markers (BTMs):

- Measurements of BTMs may provide information about expected rates of bone loss and fracture risk that cannot be obtained from measurements of BMD

- Currently, bone turnover markers cannot be recommended for the prediction of bone loss in individual patients and are not reimbursed by provincial health plans

- Bone formation markers include:

- Serum osteocalcin

- Bone-specific alkaline phosphatase (BSAP)

- C-terminal/N-terminal propeptides of type I collagen (P1CP, P1NP)

- Bone resorption markers include:

- Urinary hydroxyproline, urinary pyridinoline (PYR)

- Urinary deoxypyridinoline (D-PYR)

- Urinary collagen type I cross-linked N-telopeptide (uNTx)

- Urinary and serum collagen type I cross-linked C-telopeptide (uCTx and sCTx)

Fracture risk assessment under the CAROC (2010 version) is based upon the femoral neck T-score only

The CAROC tool stratifies women and men over age 50 into three zones of risk for major osteoporotic fracture within 10 years:

- Low (<10%)

- This group of patients does not need treatment with prescription osteoporosis medications

- Moderate (10-20%)

- This group of patients requires further assessment to determine whether prescription treatment will be necessary

- High (>20%)

- This group of patients does require prescription osteoporosis medication regardless of their BMD test results

Risk factors used in CAROC are:

- Age

- Sex

- Hip BMD

- Steroid use (increases risk level by one category if prednisone daily dose >7.5 mg/day for more than 3 months in the past year)

- Prior fragility fracture (increases risk level by one category, but hip or vertebral fracture automatically places the patient in the high-risk category)

Assessment of 10-year probability of fracture with the 2011 WHO Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX) for Canada

WHO Fracture Risk Assessment tool (FRAX) is based upon a more complete set of clinical risk factors that gives immediate calculation of the 10-year probability of a major fracture (clinical spine, wrist, proximal humerus, and hip) or hip fracture alone with or without the addition of bone mineral density (BMD) measured at the femoral neck.

Risk factors used in FRAX are:

- Age

- Sex

- Weight

- Height

- Previous fracture

- Parent fractured hip

- Current smoking

- Glucocorticoids

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Secondary osteoporosis

- Alcohol 3 or more units/day

- Bone mineral density (BMD) of the femoral neck – (optional)

Treatment

- Maintain adequate protein intake

- Adequate diet to maintain normal body weight

- Avoid excess caffeine

- Low salt intake

- Limit alcohol consumption

Calcium

- The total daily intake of elemental calcium (through diet and supplements) for individuals age 50 years and over should be 1200 mg with an upper tolerable level of 2500 mg per day

Vitamin D supplementation

- Associated with increases in bone mineral density and may reduce fracture risk, particularly when combined with adequate calcium intake

Healthy adults at low risk of vitamin D deficiency:

- Routine supplementation with 400-1000 IU (10-25 μg) vitamin D3 daily is recommended

Adults over age 50 years at moderate risk of vitamin D deficiency:

- Supplementation with 800-1000 IU (20-25 μg) vitamin D3 daily is recommended.

- To achieve optimal vitamin D status, daily supplementation with more than 1000 IU (25 μg) may be required

- Daily doses up to 2000 IU (50 μg) are safe and do not necessitate monitoring

Exercise and fall prevention

- Improves quality of life for those with osteoporosis

- Exercise should be introduced gradually to avoid injury and excessive muscle soreness. Start with shorter durations and/or lower intensities, and work up to the targets above

- Thoracic kyphosis may be reduced by a program that includes muscle strengthening, range of motion, and postural alignment exercises

Individuals with osteoporosis or at risk for osteoporosis

- Resistance training appropriate for the individual’s age and functional capacity and/or weight-bearing aerobic exercises are recommended

Individuals who have had vertebral fractures

- Exercises to enhance core stability and thus to compensate for weakness or postural abnormalities are recommended

Individuals at risk of falls

- Exercises that focus on balance, such as tai chi, or balance and gait training should be considered

Home safety assessment: effective only for those

- With severe visual impairment

- At high risk for falls

Hip protectors

- May be considered for older adults residing in long-term care facilities who are at high risk for fracture

Pharmacotherapy:

- Initiation of pharmacologic treatment for osteoporosis should be considered after assessment of absolute fracture risk by means of a validated fracture prediction tool

- Pharmacotherapy should be offered to patients at high risk (>20% probability for major osteoporotic fracture over 10 years)

- Individuals at high risk for fracture should continue osteoporosis therapy without a drug holiday

- For those with moderate fracture risk and no other risk factors, treatment should be individualized and may include pharmacologic therapy, or basic bone health measures with monitoring

- Combinations of antiresorptive agents are not recommended for fracture reduction, as they do not show greater fracture reduction than a single agent

Osteoporosis Society of Canada guidelines recommend using

- Bisphosphonates, denosumab, and raloxifene as first-line therapy for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis

- Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) as first-line therapy for the prevention of osteoporosis and as second-line therapy for the treatment of osteoporosis (although risks may outweigh benefits)

- Nasal calcitonin therapy as second-line therapy for the treatment of osteoporosis

- In addition, parathyroid hormone may be considered as first-line therapy for the treatment of severe osteoporosis

For postmenopausal women requiring osteoporosis treatment:

Bisphosphonates

- Alendronate, Risedronate, Zoledronic acid and Ibandronate

- Used as first-line therapies for prevention of hip, non-vertebral, and vertebral fractures

Human monoclonal antibody

- Denosumab

- Recommended as an alternative initial treatment for those who are at high risk for osteoporotic fractures,

- Note: The recommended dosage is 60 mg subcutaneously every 6 months.

Sclerostin inhibitor

- Romosozumab

- Recommended for up to 1 year for the reduction of the vertebral, hip, and nonvertebral fractures in those post-menopausal women who are at very high risk of fractures, such as those with severe osteoporosis (ie, low T-score < −2.5 and fractures) or multiple vertebral fractures

- Caution: Avoid in Women at high risk of cardiovascular disease and stroke

Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators

- Raloxifene, Bazedoxifene

- Can be used as first-line therapy for prevention of vertebral fractures in those post-menopausal women for whom bisphosphonates or denosumab are not appropriate or

Hormone therapy

- Estrogen, Tibolone

- Estrogen: Recommended to prevent all types of fractures in postmenopausal women at high risk of fracture with hysterectomy

- Tibolone: Recommended to prevent vertebral and nonvertebral fractures in postmenopausal women at high risk of fracture

Estrogen or Tibolone may be used when:

- Bisphosphonates or denosumab are not appropriate

- Under 60 years of age or < 10 years past menopause

- At low risk of deep vein thrombosis

- There are bothersome vasomotor symptoms

Bone metabolism regulator

- Calcitonin

- Calcitonin May be considered for prevention of vertebral fractures for menopausal women intolerant of first-line therapies (lower efficacy than other options)

Parathyroid Hormone and Parathyroid Hormone-Related Protein Analogs

- Teriparatide, Abaloparatide

- Recommended for up to 2 years to prevent vertebral and non-vertebral fractures in postmenopausal women at high risk of fracture, e.g. severe or multiple vertebral fractures

Calcium and Vitamin D

- Can be used as an adjunct to osteoporosis therapies or in those who are intolerant to other osteoporosis therapies

For men requiring osteoporosis treatment:

Alendronate, Risedronate, and Zoledronic acid

- Can be used as first-line therapies for prevention of fractures

Individuals on long-term glucocorticoid therapy:

- A bisphosphonate (alendronate, risedronate, zoledronic acid) should be initiated at the beginning and should be continued for at least the duration of the glucocorticoid therapy in individuals over age 50 years who are on long-term glucocorticoid therapy (three months cumulative therapy during the preceding year at a prednisone-equivalent dose >7.5 mg daily), use with caution in premenopausal women

- Teriparatide should be considered for those at high risk for fracture who are taking glucocorticoids (three months cumulative therapy during the preceding year at a prednisone-equivalent dose >7.5 mg daily)

- For long-term glucocorticoid users who are intolerant of first-line therapies, calcitonin or etidronate may be considered to prevent loss of bone mineral density

Patients with breast cancer:

Women receiving aromatase inhibitor (AI) therapy

- Zoledronic acid, denosumab, and risedronate have been demonstrated to reduce AI-associated BMD loss

Women taking adjuvant anastrozole for early breast cancer

- Risedronate resulted in significant increase in the lumbar spine and total hip BMD

Patients with prostate cancer:

Men receiving androgen deprivation therapy (ADT)

- Denosumab showed a decreased cumulative incidence of new vertebral fractures at 36 months (ARR 2.4%)

Osteoporosis prevention strategies in premenopausal women:

- Identify risk factors

- Adequate calcium and vitamin D intake

- Reduced intake of caffeine and alcohol

- Weight-bearing and resistance exercises

- Tobacco avoidance

Osteoporosis treatment strategies in premenopausal women:

- Osteoporosis is uncommon in premenopausal women, and most cases have a secondary cause

- Treat the underlying disease process or discontinue the inciting medication, if possible

- Use of bisphosphonates is approved in premenopausal women, but exercise caution in this population because there are limited data about long-term use

Osteoporotic pain:

Osteoporotic patients experience pain and are managed accordingly. The following options are available:

- A brace or support (only as a temporary measure)

- Analgesics

- Applications of heat and ice

- Warm showers or hot packs can ease stiff muscles

- Cold can numb the painful area and can also reduce swelling and inflammation

- Gentle massage

- Acupuncture

- Light stretching/strengthening exercises

- Avoid heavy lifting

- Physical activity

- Bed rest should be minimized

- Antidepressant medication

- Sometimes prescribed to help people cope with chronic pain

- Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS)

- Consistent, carefully designed weight-bearing exercise should be encouraged

- In some cases, vertebroplasty, sometimes preceded by kyphoplasty, can relieve severe pain of an acute vertebral fracture

- In vertebroplasty, methyl methacrylate is injected into the vertebral body

- In kyphoplasty, the vertebral body is expanded with a balloon, and then injected with cement

Monitoring effectiveness of treatment:

- Repeat central DEXA scan is an important component of osteoporosis management

- Identify individuals with continued BMD loss, despite appropriate osteoporosis treatment

- Repeat BMD assessments after 18 months-two years of therapy. If BMD has stabilized or increased, further BMD testing is not necessary

- The following techniques may be used to monitor the effectiveness of treatment:

- Central DEXA: Central DEXA assessment of the hip or spine is currently the “gold standard” for serial assessment of BMD

- Quantitative computed tomography (QCT) measurement of vertebral trabecular BMD of the lumbar spine can be used to monitor age, disease and treatment-related BMD changes in men and women (not widely available, mainly a research tool)

- Stable or improved BMD is consistent with successful treatment

– When to refer patients for specialized consultation and care

– Institute of Medicine (IOM) Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs) for calcium

– Institute of Medicine (IOM) Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs) for vitamin D[/cq_vc_tab_item][cq_vc_tab_item tabtitle=”Medication Dose”]MEDICATIONS

- Alendronate (oral)

- Etidronate (oral)

- Ibandronate (oral / IV)

- Risedronate (oral)

- Zoledronic acid (IV)

Mechanisms:

- Inhibits bone resorption via actions on osteoclasts or on osteoclast precursors

- Decrease the rate of bone resorption, leading to an indirect increase in bone mineral density

Doses:

Prevention of postmenopausal osteoporosis

Alendronate

- 5 mg PO daily

Etidronate

- 90-day cycle; etidronate 400 mg PO daily for 14 days, then calcium carbonate 1250 mg PO daily for 76 days (usually other agents preferred)

Ibandronate

- Dosage (oral): 150 mg PO once monthly on the same day each month

Risedronate

- 5 mg PO daily or 35 mg PO once weekly

Zoledronic acid

- 5 mg IV once

Treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis

Alendronate

- 10 mg PO daily or 70 mg PO once weekly or 70 mg/2800 IU Vitamin D or 70 mg/5600 IU vitamin D once weekly

Etidronate

- 90-day cycle; etidronate 400 mg PO daily for 14 days, then calcium carbonate 1250 mg daily for 76 days (usually other agents preferred)

Ibandronate

- Dosage (oral): 150 mg PO once monthly on the same day each month

- Dosage (IV): 3 mg IV every 3 months administered over a period of 15 to 30 seconds

Risedronate

- 5 mg PO daily or 35 mg PO once weekly or 150 mg PO once monthly on the same calendar day each month or risedronate-EDTA 35 mg once weekly with breakfast

Zoledronic acid

- 5 mg IV once yearly

Treatment of primary osteoporosis in men

Alendronate

- 10 mg PO daily or 70 mg PO once weekly

Risedronate

- 35 mg PO once weekly

Zoledronic acid

- 5 mg once yearly IV

Prevention and treatment of corticosteroid-induced osteoporosis in men and women

Alendronate

- 5 mg PO daily (postmenopausal women not taking estrogen: 10 mg PO daily or 70 mg PO weekly)

Etidronate

- 90-day cycle; etidronate 400 mg PO daily for 14 days, then calcium carbonate 1250 mg daily for 76 days

- Note: Use for prevention only

Risedronate

- 5 mg PO daily or 35 mg PO weekly or 150 mg PO monthly

Zoledronic acid

- 5 mg IV once yearly

Selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERMs):

- Bazedoxifene

- Raloxifene

Mechanisms:

- Reduces resorption of bone by inhibiting the formation and action of osteoclasts, increasing bone mineral density and decreases overall bone turnover

- It also has estrogen antagonist effects in uterine and breast tissues

- Bazedoxifene demonstrates both tissue-selective estrogen receptor agonist and antagonist activity

Doses:

Treatment and prevention of postmenopausal osteoporosis

Bazedoxifene

- Dosage(oral): Bazedoxifene 20 mg in fixed combination with conjugated estrogens 0.45 mg once daily at the same time each day

Raloxifene

- Dosage: 60 mg PO once daily; administered any time of day without regard to meals

- Calcitonin

Mechanisms:

- Functionally antagonizes the effects of parathyroid hormone

- Directly inhibits osteoclastic bone resorption

- Increases the renal excretion of calcium, phosphorus, sodium, magnesium, and potassium by decreasing tubular reabsorption

- Increases the jejunal secretion of water, sodium, potassium, and chloride

Doses:

Postmenopausal osteoporosis

Calcitonin (intranasal)

- One spray (200 IU i.e. 0.2 µg) per day, alternating nostrils daily

Calcitonin (injectable)

- Subcutaneous/ IM 100 units every other day with supplemental calcium and adequate vitamin D

Note: Recommended in conjunction with adequate calcium (at least 1000 mg elemental calcium per day) and vitamin D (400 IU per day) intake.

- Romosozumab

Mechanisms:

- Binds and inhibits sclerostin, a negative regulator of bone formation

- Increasing bone formation and decreasing bone resorption

- Increases trabecular and cortical bone mass

- Improves bone structure and strength

Doses:

Postmenopausal osteoporosis

Romosozumab

- Dosage (subcutaneous): The recommended dose is two injections 105 mg/1.17 mL solution each, one after the other once monthly for 12 months

Caution:

- Avoid in Women at high risk of cardiovascular disease and stroke

- Patients should be adequately supplemented with calcium and vitamin D before and during treatment

- Denosumab

Mechanisms:

- Denosumab binds to RANKL, preventing RANKL from activating its only receptor, RANK, on the surface of osteoclasts and their precursors

- Leads to decreased bone resorption and increased bone mass in osteoporosis

- In solid tumors with bony metastases, RANKL inhibition decreases osteoclastic activity leading to decreased skeletal-related events and tumor-induced bone destruction

Doses:

Postmenopausal osteoporosis

Denosumab

- Single injection of 60 mg SC, once every 6 months

Note: Recommended in conjunction with adequate calcium and vitamin D intake.

Parathyroid hormone analog-Bone formation agent:

- Abaloparatide

- Teriparatide

Mechanisms:

- Pharmacologic activity is similar to the physiologic activity of parathyroid hormone (PTH)

- It stimulates osteoblast function, increases gastrointestinal calcium absorption, and increases renal tubular reabsorption of calcium

- Results in increased bone mineral density, bone mass, and strength

- Decrease osteoporosis-related fractures in postmenopausal women

Doses:

Abaloparatide

- 80 mcg subcutaneously once daily

Teriparatide

- 20 µg SC once a day into the thigh or abdominal wall for a maximum of 24 months

Note: Supplemental calcium and vitamin D is recommended if dietary intake is inadequate.

- Conjugated estrogens

- Conjugated estrogens and medroxyprogesterone

- Tibolone

Mechanisms:

Conjugated estrogens

- Estrogens modulate pituitary gonadotropin hormone secretion through a negative feedback mechanism; estrogen replacement reduces elevated levels of these hormones in postmenopausal women

- Conjugated estrogens reduce bone resorption and retard postmenopausal bone loss

Medroxyprogesterone (MPA)

- When administered with conjugated estrogens, MPA reduces the incidence of endometrial hyperplasia and risk of adenocarcinoma

Tibolone

- Converted into three major metabolites: 3 alpha- and 3 beta-hydroxy-tibolone, which have oestrogenic effects, and the Delta(4)-isomer, which has progestogenic and androgenic effects

- Bone-conserving effects occur due to estradiol receptor activation

Doses:

Prevention of postmenopausal osteoporosis

Conjugated estrogens

- Dosage: 0.625 mg PO once daily

Note: Premarin should be prescribed with an appropriate dosage of a progestin for women with intact uteri, in order to prevent endometrial hyperplasia/carcinoma

Conjugated Estrogens (CE) and Medroxyprogesterone (MPA)

Continuous therapy

- Dosage: One conjugated estrogen 0.625 mg/ MPA 2.5 mg tablet OR one conjugated estrogens 0.625 mg/ MPA 5.0 mg tablet taken at the same time daily for 28 days

Note: Starting dose of 0.625 mg/2.5 mg is appropriate for most women entering menopause. May consider increasing the dose to the 0.625 mg/5.0 mg therapy if amenorrhea is not achieved within a few months of initiating therapy. Once amenorrhea is achieved, consider dose reduction to 2.5 mg

Cyclic therapy

- Dosage: One maroon 0.625 mg conjugated estrogens tablet daily for 28 days at the same time each day and one peach 10 mg MPA tablet daily at the same time from day 15-28 of a 28-day cycle

Note: May be used where a higher dose MPA is needed and regular withdrawal bleeding is medically appropriate on an individualized basis

Tibolone

- Dosage: 2.5 mg PO once daily

[/cq_vc_tab_item][/cq_vc_tabs]

Physician Resources

1. Tips for patient care

Risk factor management:

- Educate patient about triggers and management

- Discuss primary prevention of fractures

- Diet to maintain normal body weight

- Facilitate smoking cessation

- Reduce or eliminate caffeinated and alcoholic beverages from the diet

- Reduce salt intake

- Encourage recommended calcium and vitamin D intake

- Regular exercise

- Advise and refer to physiotherapists or kinesiologists, to help with the development of appropriate exercise regimen

- Advise use of assistive devices to help with ambulation, balance, lifting and reaching, if required

- Educate to take preventative measures to avoid injury and excessive muscle soreness

- Advise patients to avoid bending forward and exercising with trunk in flexion, especially in combination with twisting

Monitoring:

- Identify individuals with continued BMD loss, despite appropriate osteoporosis treatment

- Repeat BMD assessments after 1-2 years of pharmacologic therapy, or every two-five years in untreated patients,, but recognize that testing more frequently may be warranted in certain clinical situations

- Consider concurrent risk factors and disease states with the prescribed therapy

Medications:

- Advise patient to establish a prescribed routine for pill-taking

- Evaluate risk and benefit ratio of prescribed therapy

- Simplify the dosing regimen where possible

- Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERM) are contraindicated in women who have a history of thromboembolic events

- Alendronate and risedronate are best taken first thing in the morning with plain a glass of plain water, at least 1/2 hour before eating. The patient recommended staying upright (don’t bend or lie down) for 1/2 hour prior to eating. It is best to avoid using a calcium supplement with breakfast on that day

- Evaluate cost and affordability and insurance coverage when prescribing as this could affect compliance

Social and Stress factors:

- Discuss available therapeutic options and their risk and benefits with the patient

- Counsel patient and family to help lessen the psychological stress, including the potential social embarrassment of having to use a walking aid and other assistive devices

Alerts:

- Fragility fractures are a warning sign of osteoporosis and must be investigated

- Corticosteroid-induced bone loss is believed to be most rapid in the first few months of treatment, especially within the spine

- Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERM) is contraindicated in women who have a history of thromboembolic events

- Women with breast cancer receiving aromatase inhibitor (AI) therapy may have increased BMD loss and fractures

- Men who receive androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) for prostate cancer are at higher risk for fracture

Activities (physical, mental, others):

- Patients advised to participates in activities of daily living but avoid overwork and fatigue

- Avoid a sedentary lifestyle – encourage regular exercise and structured exercise program

- Mobilize – avoid prolonged sitting/resting

2. Scales and Tables

References

Core Resources:

- Compendium of Pharmaceuticals and Specialties (CPS). Canadian Pharmacist Association. Toronto: Webcom Inc. 2012

- Day RA, Paul P, Williams B, et al (eds). Brunner & Suddarth’s Textbook of Canadian Medical-Surgical Nursing. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2010

- Foster C, Mistry NF, Peddi PF, Sharma S, eds. The Washington Manual of Medical Therapeutics. 33rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010

- Gray J, ed. Therapeutic Choices. Canadian Pharmacists Association. 6th ed. Toronto: Webcom Inc. 2011

- Jeremiah MP, Unwin BK, Greenawald MH, et al. Diagnosis and Management of Osteoporosis. Am Fam Physician 2015;92(4):261-8

- Katzung BG, Masters SB, Trevor AJ, eds. Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. 11th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2009

- Longo D, Fauci A, Kasper D, et al (eds). Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 18th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2011

- McPhee SJ, Papadakis MA, eds. Current Medical Diagnosis & Treatment. 49th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2010

- Pagana KD, Pagana TJ eds. Mosby’s Diagnostic and Laboratory Test Reference. 9th ed. St. Louis: Elsevier-Mosby; 2009

- Papaioannou A, Morin S, Cheung AM, et al. 2010 clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in Canada: summary. CMAJ 2010, 182(17):1864-73

- Papaioannou A, Santesso N, Morin SN, et al. Recommendations for Preventing Fracture in Long-Term Care. CMAJ 2015;187(15):1135-1144. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.141331

- Skidmore-Roth L. ed. Mosby’s drug guide for nurses. 9th ed. St. Louis: Elsevier-Mosby; 2011

- Skidmore-Roth L, ed. Mosby’s nursing drug reference. 24th ed. St. Louis: Elsevier-Mosby; 2011

- Online resource/weblinks:

- http://www.merckmanuals.com

- http://www.osteoporosis.ca

- http://www.rheuminfo.com

Online Pharmacological Resources:

- e-Therapeutics

- Lexicomp

- RxList

- Epocrates

Journals/Clinical Trials:

- Bono CM, Einhorn TA. Overview of osteoporosis: pathophysiology and determinants of bone strength. Eur Spine J. Oct 2003;12 Suppl 2:S90-6

- Bone HG,McClung MR, Roux C et al.Odanacatib, a cathepsin-K inhibitor for osteoporosis: A two-year study in postmenopausal women with low bone density. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 2010;25: 937-947

- Cadarette SM, Jaglal SB, Kreiger N, et al. Development and validation of the Osteoporosis Risk Assessment Instrument to facilitate selection of women for bone densitometry. CMAJ 2000; 162:1289

- Cadarette SM, Jaglal SB, Murray TM, et al. Evaluation of decision rules for referring women for bone densitometry by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry. JAMA 2001; 286:57

- Cooper C, Campion G, Melton LJ 3rd. Hip fractures in the elderly: a world-wide projection. Osteoporosis Int. Nov 1992;2

- Cummings SR, Nevitt MC, Browner WS, et al. Risk factors for hip fracture in white women. N Engl J Med 1995; 332:767

- Cummings SR, Melton LJ. Epidemiology and outcomes of osteoporotic fractures. Lancet. May 18 2002;359(9319):1761-7

- Eastell R, Rosen CJ, Black DM, et al. Pharmacological Management of Osteoporosis in Postmenopausal Women: An Endocrine Society* Clinical Practice Guideline. Clin Endocrinol Metab 2019;104(5):1595-1622. doi: 10.1210/jc.2019-00221

- Gullberg B, Johnell O, Kanis JA. World-wide projections for hip fracture. Osteoporos Int 1997; 7:407.

- Jaglal SB, Weller I, Mamdani M, et al. Population trends in BMD testing, treatment, and hip and wrist fracture rates: are the hip fracture projections wrong?. J Bone Miner Res 2005; 20:898

- Johansson H, Oden A, Johnell O, et al. Optimization of BMD measurements to identify high risk groups for treatment–a test analysis. J Bone Miner Res 2004; 19:906

- Johnell O, Kanis JA, Black DM, et al. Associations between baseline risk factors and vertebral fracture risk in the Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation (MORE) Study. J Bone Miner Res 2004; 19:764

- Johnell O, Kanis, JA. An estimate of the worldwide prevalence and disability associated with osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int 2006; 17:1726

- Kannus P, Niemi S, Parkkari J, et al. Nationwide decline in incidence of hip fracture. J Bone Miner Res 2006; 21:1836

- Leslie WD, O’Donnell S, Jean S, et al. Trends in hip fracture rates in Canada. JAMA 2009; 302:883

- Lydick E, Cook K, Turpin J, et al. Development and validation of a simple questionnaire to facilitate identification of women likely to have low bone density. Am J Manag Care 1998; 4:37

- Mauck KF, Cuddihy MT, Atkinson EJ, Melton LJ, 3rd. Use of clinical prediction rules in detecting osteoporosis in a population-based sample of postmenopausal women. Arch Intern Med 2005;

- Mora S, Gilsanz V. Establishment of peak bone mass. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. Mar 2003;32(1):39-63

- National Osteoporosis Foundation. Clinician’s Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. Available at http://www.nof.org/professionals/Clinicians_Guide.htm. Accessed May 5, 2008

- Nymark T, Lauritsen JM, Ovesen O, et al. Decreasing incidence of hip fracture in the Funen County, Denmark. Acta Orthop 2006; 77:109

- Perez-Castrillon JL, Pinacho F, De Luis D et al. Odanacatib, a New Drug for the Treatment of Osteoporosis: Review of the Results in Postmenopausal Women Journal of Osteoporosis 2010; 2010), Article ID 401581, 5 pages

doi:10.4061/2010/401581 - Raisz LG. Pathogenesis of osteoporosis: concepts, conflicts, and prospects. J Clin Invest. Dec 2005;115(12):3318-25

- Ringe JD, Farahmand P. Advances in the management of corticosteroid-induced osteoporosis with bisphosphonates. Clin Rheumatol. Apr 2007;26(4):474-84

- Rogmark C, Sernbo I, Johnell O, Nilsson JA. Incidence of hip fractures in Malmo, Sweden, 1992-1995. A trend-break. Acta Orthop Scand 1999; 70:19

- Seeman E, Delmas PD. Bone quality–the material and structural basis of bone strength and fragility. N Engl J Med. May 25 2006;354(21):2250-61