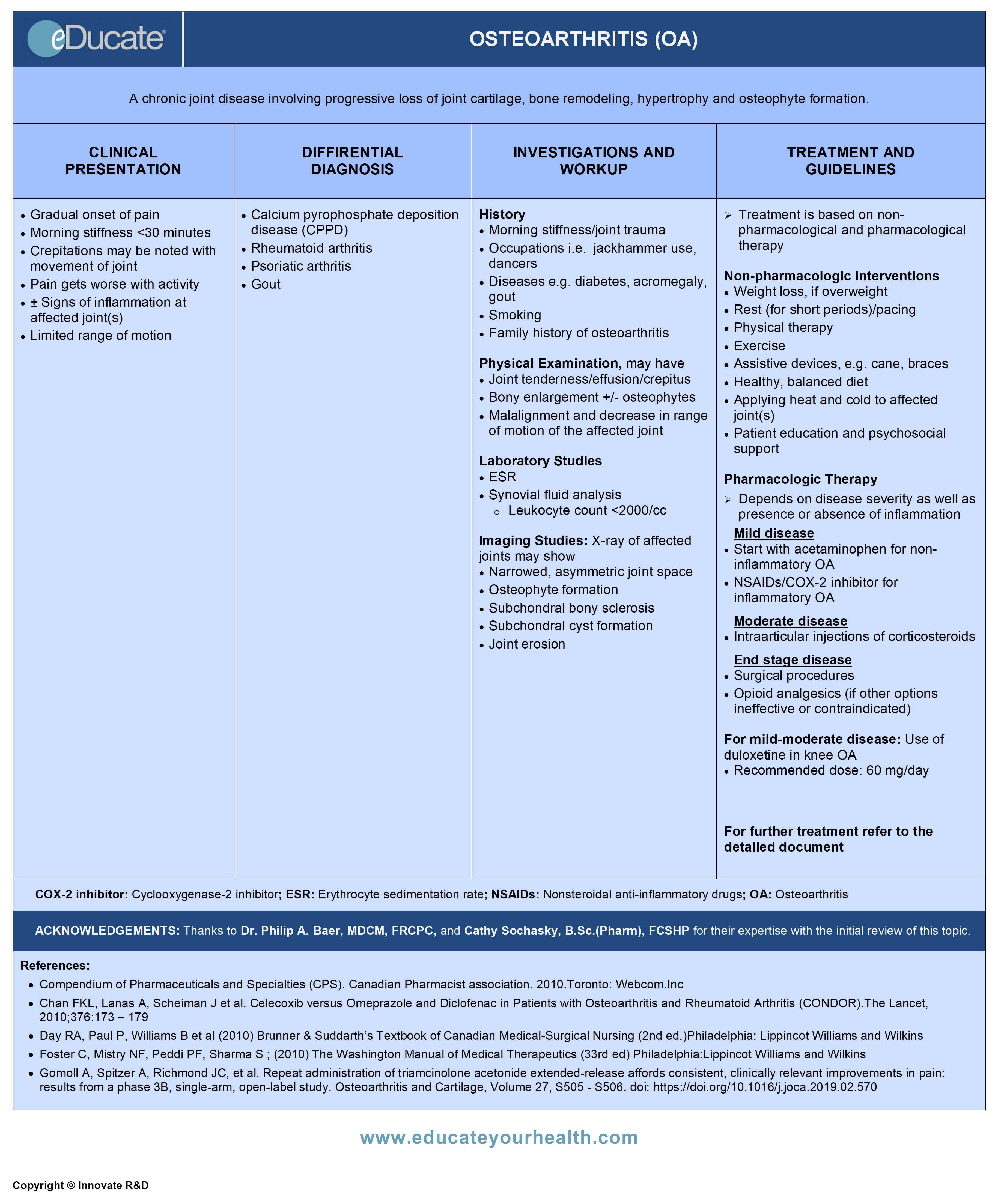

Osteoarthritis (OA)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

Thanks to Dr. Philip A. Baer, MDCM, FRCPC, Internal medicine (Rheumatology), Chair, OMA Section on Rheumatology, VP, Ontario Rheumatology Association, ON Canada, and Cathy Sochasky, B.Sc.(Pharm), FCSHP, Drug Information Pharmacist, Health Sciences Centre, Winnipeg, MB Canada for their expertise with the initial review of this topic.

Definition

A chronic joint disease involving progressive loss of joint cartilage, bone remodeling, hypertrophy and osteophyte formation.

Etiology

Biomechanical, biochemical, inflammatory, and immunologic factors are implicated in the pathogenesis.

Idiopathic OA

- Commonly seen with no underlying condition, often localized to distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints of hands, first metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joints, hip or knee; or may be generalized involving 3 or more joints

Secondary OA

Conditions which may cause or enhance the risk of developing OA include:

- Developmental disorders of joints

- Calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate deposition disease (CPPD)

- Rheumatoid arthritis, gouty arthritis, paget’s disease

- Diabetes mellitus, acromegaly, hypothyroidism, neuropathic (Charcot) arthropathy, hemochromatosis

Epidemiology

Approximately 10% of Canadians have OA

- Leading cause of work disability in those who are <65 years of age in North America

- Symptoms often arise >40 years of age

- Shows female preponderance between 40-70 years of age

- After the age >70 years, M and F equally affected

- ~80% of people will have radiographic evidence of OA after the age of 65 years

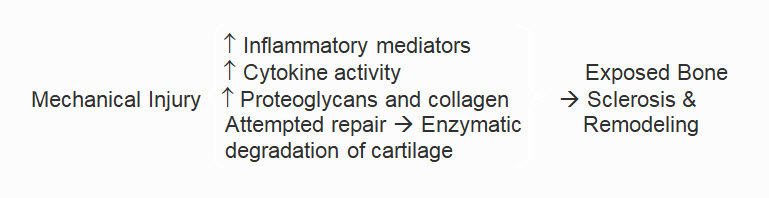

Pathophysiology

- Entire joint involved, including cartilage, subchondral bone and synovium

- Begins with tissue damage usually from mechanical injury (e.g. torn meniscus)

- Tissue damage leads to attempted repair through chondrocyte activation, which initially increases production of proteoglycans and collagen

- Efforts at repair also stimulate the release of enzymes that degrade cartilage as well as other inflammatory mediators, including prostaglandins

- Failure of repair processes combined with inflammation lead to cartilage degradation. Eventually chondrocytes undergo apoptosis

- Cartilage destruction exposes bone which then becomes eburnated and sclerotic

Pathological Findings:

Macroscopic:

- Patchy cartilage damage and bone hypertrophy

- Subchondral bone microfractures, sclerosis with osteophyte formation

Histology:

- Edema of the extracellular matrix and cartilage micro cracks

- Diminished proteoglycan staining

- Fissuring and pitting of the subchondral bone

- Articular surface irregularity due to clefts and erosions

Clinical Presentation

Main symptom associated with OA is pain, which is typically exacerbated by activity and relieved by rest.

- Gradual onset of pain

- Morning stiffness always <20-30 minutes

- Crepitations may be noted with the movement of joint

- Joint involvement progresses slowly and irreversibly

Differential Diagnosis

- Calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease (CPPD)

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Psoriatic arthritis

- Gout

Investigation and Workup

- Diagnosis is based on:

- Classical symptoms

- Physical examination

- Labs

- Imaging

- The involvement of joints that are not usually affected by idiopathic disease (e.g. the shoulder, elbow, wrist, and ankle) suggests other etiologies

- Severe acute onset of pain is unlikely, joint aspiration is recommended to exclude other causes (gout, pseudogout, infection)

History of:

- Morning stiffness

- Joint trauma

- Work or hobby-induced trauma through repetitive stressful joint movements e.g. dancers

- Smoking

- Presence of diabetes, acromegaly, gout, other forms of inflammatory arthritis

- Family history

Physical examination:

Common findings that may be present:

- Joint tenderness with or without inflammation

- Joint effusion/crepitus

- Osteophytes may be palpable

- Joint malalignment and decrease in range of motion

Laboratory studies

There is no blood test to diagnose osteoarthritis. The following tests may be ordered when history and physical findings dictate:

- CBC

- Creatinine: If considering treatment with NSAIDs

- ESR/C-reactive protein

- ANA: When considering connective tissue disease

- RF factor

- Synovial fluid analysis

- Joint fluid will have a leukocyte count <2000/ml

- (WBC= conventional units are 2000×109/L)

Imaging studies:

- Usually recommended for persistent unexplained pain

- Always mention on the requisition that the X-rays are for OA

- X-ray of affected joints typically shows:

- Osteophyte formation

- Subchondral bony sclerosis

- Subchondral cyst formation

- Erosions may occur on the surface of distal and proximal interphalangeal joints when OA is associated with inflammation (erosive osteoarthritis)

Treatment

- The combination of diet and exercise is effective in reducing weight and disease progression

2. Rest:

- Recommended when acute pain and inflammation are present (~12 to 24 hrs)

- Prolonged rest may lead to muscle atrophy and restricted joint movements hence alternating activity and rest is important

- Pacing of activities is important

3. Physical therapy and assistive devices:

- May help to improve outcome and decrease pain by:

- Improving flexibility

- Strengthening muscles

- Reducing load on the affected joints by assistive devices (orthotics, cane, braces)

- Unloading the joints: Use of cushioned, supportive shoes can decrease the impact of load on joints

- Manual therapy: Stretching and joint manipulation may be more beneficial for hip OA

- Braces and splints: Provide symptomatic improvement specifically in knee and wrist joint

- Patellofemoral syndrome: Occurs due to patellar misalignment. Symptomatic benefits can be achieved with knee bracing and taping as well as quadriceps strengthening

4. Exercise:

Deficiencies in gait, strength, flexibility, aerobic power, and exercise capacity can be safely reversed with a variety of exercise regimens

- Exercise programs: High-intensity aerobic exercise benefits those in mild disease

- Symptomatic relief: Motion and strengthening exercises can reduce pain and increase mobility in patients with OA

- Joint protection: Can be achieved by exercising in warm water

- Disability prevention: Exercise does not need to be intense in order to improve mobility and disability. The benefits that can be achieved are:

- Improvement in pain and mobility

- Reversal of muscular atrophy

- Increase bone mineral density, which decreases the risk of osteoporotic fractures

Aerobic versus resistance (strengthening) exercise: Both have moderate effects on pain and range of motion

5. Group exercise programs:

The Arthritis Society of Canada (www.arthritis.ca) provides many programs, including group exercise, aqua-fit and Arthritis Self-Management Programs (ASMP)

6. Patient compliance:

Can be maximized through several techniques, including

- Simplifying regimens and setting attainable goals

- Emphasizing and educating the importance and benefits of exercise

7. Heat and cold:

- Moist heat and superficial cold both can raise the pain threshold and decrease muscle spasm

8. Patient education and psychosocial support:

Assess, evaluate, and educate about the effects of OA which include:

- Physical limitations

- Feelings of frustration and dependency

- Depression

- Decreased motivation to comply with diet exercise and medication

9. Other:

- Acupuncture, massage, herbs, relaxation techniques, counter-irritants, and mud pack therapies have been tried with varying degrees of response

Pharmacologic therapy

Therapy depends on disease severity as well as presence or absence of inflammation.

Both inflammatory and non-inflammatory OA can be polyarticular, oligoarticular, or monoarticular. A generalized approach to treatment is as follows:

1. Mild disease:

- OA ± inflammation is initially managed using a non-pharmacological approach

- If symptoms persist, addition of simple analgesics on a PRN basis is advised (acetaminophen for non-inflammatory OA and NSAIDs for inflammatory OA)

2. Moderate disease:

- Scheduled/regular dosing of NSAIDs and/or acetaminophen

- Intraarticular injections of corticosteroids may be helpful (rapid recovery lasting for 1-3 months)

- Viscosupplementation for knee joint – requires 1-3 injections although expensive, show 60-75% response, and effect lasts up to 6-9 months

3. End-stage disease:

- For both inflammatory and non-inflammatory OA, a surgical approach such as total joint replacement may be indicated. If surgery is not an option then opioid analgesics may be considered if other medications are ineffective or contra-indicated

- Consider opioid analgesics if surgery is not an option and other medications are ineffective

For mild to moderate disease consider the following analgesic options:

- Acetaminophen up to 1000 mg PO QID for short-term use. Chronic dose usually restricted to 2.6-3.2 g/day

- Topical NSAIDs provide short-term benefit in knee OA

- If acetaminophen or topical NSAIDs are ineffective, then the addition or substitution by an oral NSAID/COX-2 inhibitor should be considered. Use the lowest effective dose for the shortest possible period of time. Prolonged use is not usually recommended

- Oral corticosteroids have no role. However, intra-articular depot corticosteroids in relieving pain and increasing joint flexibility

Note:

For mild-moderate disease:

- Duloxetine can be use in knee OA

- Recommended dose: 60 mg/day

Ref: Chappell AS, Ossanna MJ, et al. Pain. 2009; 46:253-60.

Topical

- Topical NSAID use may reduce the side effects of oral NSAIDs

Intra-articular:

- Intra-articular depot corticosteroids help relieve pain and increase joint flexibility. The amount of agent generally used depends on the size of the joint. Methylprednisolone 10 mg in small joints while 40 mg in large joints like hip Joint

- Hyaluronate and hylan G-F 20, agents known as viscosupplements, administered over time through intra-articular injections into the knee, known to have some benefits

- Triamcinolone acetonide extended-release intra-articular injection is a nonopioid that provides knee pain relief over 12 weeks

C) Surgical intervention:

Only recommended when pain becomes intolerable and mobility is compromised leading to poor quality of life. Options include

- Osteotomy

- Debridement and joint fusion

- Arthroscopy and arthroplasty

[/cq_vc_tab_item][cq_vc_tab_item tabtitle=”Medication Dose”]

- Salicylates

- Acetic acid derivatives

- Enolic acid (oxicam) derivatives

- Napthylkanone derivatives

- Propionic acid derivatives (profens)

- COX-2 inhibitors

Mechanism:

- Prostaglandins are common locally produced chemicals mediating pain, fever, and inflammation

- These drugs reversibly inhibit cyclooxygenase-1 and 2 (COX-1 and 2) enzymes

- This results in decreased formation of prostaglandin precursors

- Acetylsalicylic acid in addition to the above mechanisms, irreversibly interferes with the production of thromboxane A2 within the platelet, thus inhibiting platelet aggregation

Dose:

Salicylates

Aspirin:

- 325-650 mg PO every 4-6 hours; Max. 4 g/day

Diflunisal:

- 500-1000 mg/day PO in 2 divided doses; Max. daily dose 1.5 g

Renal impairment:

- Decrease the dose by 50% if ClCr <50 mL/minute

Acetic acid derivatives

Diclofenac

- Immediate-release: 150 mg PO daily in 3-4 divided doses; Max. 150 mg/day

- Slow-release: 150-200 mg PO daily in 2-4 divided doses

- Canadian labeling: 150 mg/day PO in 3 divided doses (75-150 mg/day of slow-release tablet)

- Rectal suppository: 50-100 mg/day, as single dose then maximum 100 mg/day or combined dose (rectal + oral) is 150 mg/day

Diclofenac/Misoprostol

- 50 mg/200 mcg and 75 mg/200 mcg tablets; Max. 150 mg diclofenac/day

- Note: Misoprostol 800 mcg is the maximum daily dose. Not recommended in advanced renal disease

Etodolac

- Immediate-release: 400-500 mg PO BID; or 300 mg 2-3 times/day; Max. 1000 mg/day

- Extended-release: 400-1000 mg once daily

Indomethacin

- Immediate-release: 25 mg PO BID or TID; Max. 200 mg/day

- Extended-release: 75 mg PO daily; may increase 75 mg PO BID if needed; Max. 150 mg/day

- Rectal: 25 mg 2-3 times daily

Sulindac

- 150 mg PO BID; Max.400 mg/day

Enolic acid (oxicam) derivatives

Meloxicam:

- 7.5 mg PO daily; may increase for additional benefit to 15 mg/day; Max. 15 mg/day

Piroxicam

- 10-20 mg PO in 1-2 divided doses; Max. 20 mg/day

Tenoxicam:

- 10-20 mg PO daily for 7-14 days

- 20 mg IM / IV daily for 1-2 days

Napthylkanone derivatives

Nabumetone:

- 1 g PO daily; may increase up to 2 g PO in 2 divided doses

Renal impairment:

- ClCr 30-49 mL/minute: 750 mg/day may increase up to 1500 mg/day

Propionic acid derivatives (profens)

Fenoprofen:

- 300-600 mg PO TID or QID; Max. 3.2 g/day

Flurbiprofen

- 200-300 mg/day in 2, 3, or 4 divided doses. Do not administer more than 100 mg per single dose; Max 300 mg/day

Ibuprofen

- 200-800 mg PO 3-4 times a day; Max dose 3.2 g/day; usual dose 800 mg PO BID

Ketoprofen

- Regular release: 50 mg PO QID or 75 mg PO TID; Max. 300 mg/day

- Extended-release: 200 mg PO daily

Renal impairment:

- Mild: Maximum dose is 150 mg/day

- Severe (ClCr <25mL/min): Maximum dose is 100 mg/day

Naproxen

- Regular release: 500-1000 mg/day in 2 divided doses; may increase to 1.5 g/day

Oxaprozin

- 600-1200 mg PO daily; Max. 1800 mg/day. Titrate it to a lowest possible dose

COX-2 Inhibitors

Celecoxib:

- 200 mg PO daily as a single dose or in 2 divided doses; Max. 200 mg/day

- Acetaminophen

Mechanism:

- Analgesic action: Inhibits the synthesis of prostaglandins in the central nervous system

- Antipyretic action: Inhibits the hypothalamic heat-regulating center

Dose:

Acetaminophen:

- 325-650 mg PO or 1000 mg PO TID or QID; not to exceed 1 g/dose; Max. 4 g/day

- Morphine

- Oxycodone

- Tramadol

- Codeine

- Tapentadol

- Buprenorphine transdermal patch

Mechanism:

- Bind to opioid receptors in the CNS

- Inhibit reuptake of serotonin and/or norepinephrine in the CNS (tramadol, tapentadol)

- Inhibit ascending pain pathways, and alter the perception of and response to pain

Dose:

Morphine:

- Start 10 mg PO every 4-6 hours in opiate naïve patients; patients with previous exposure may need higher doses

Oxycodone:

- Immediate release: 5-10 mg PO every 4-6 hours

- Controlled release: 10-20 mg PO BID or higher as needed

Tramadol:

- Conventional release: 25 mg PO four times daily; may increase total daily dosage by 50 mg every 3 days as tolerated, up to 200 mg daily (50 mg four times daily)

- After titration, 50-100 mg can be given every 4-6 hours, up to Max. of 400 mg daily

- Extended-release: 100 mg PO daily; may increase dose in 100 mg increments every 5 days as needed; Max. 300 mg/day

Tapentadol:

Controlled release:

- Start 50 mg PO BID may titrate to effective dose

Immediate release:

- Day 1: 50-100 mg PO every 4-6 hours as needed; may administer the second dose after an hour of the first dose; Max. dose on day 1: 700 mg

- Day 2 and onwards: 50-100 mg PO every 4-6 hours as needed; Max. 600 mg/day

Codeine:

- Regular release: Start at 30 mg PO every 4-6 hours; maintain at 15-120 mg PO every 4-6 hours as needed; may start with higher initial dose in patients with prior opiate exposure

- Controlled release: 50-300 mg PO BID; may administer higher dose in opioid-tolerant patients

Buprenorphine (Transdermal):

- Opioid-naive patients: Initially apply 5 mcg/hour applied once every 7 days; maintain at 5-20 mcg/hour patch once every 7 days; Max. 20 mcg/hour

- Opioid-experienced patients (oral morphine equivalent

<30 mg/day): Initially apply 5 mcg/hour once every 7 days; Max. 20 mcg/hour - Opioid-experienced patients (oral morphine equivalent

30-80 mg/day): Initially apply 10 mcg/hour once every 7 days; Max. 20 mcg/hour

Note: Prior to starting therapy, taper dose for up to 7 days to ≤30 mg/day of oral morphine

- Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) Agonist

- Capsaicin

- Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Agents

- Diclofenac sodium

Mechanism:

Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 1 (TRPV1)

Agonist

- Exact mechanism of action unknown

- Selectively binds nerve membrane TRPV1 receptor

- Stimulates and desensitizes cutaneous nociceptive neurons

- Also depletes Substance P, which helps in reducing pain impulse transmission from periphery to the CNS

Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Agents

- Prostaglandins mediate the production of pain, fever, and inflammation

- These drugs inhibit cyclooxygenase-1 and 2 (COX-1 and 2) enzymes

- This results in decreased formation of prostaglandin precursors

Dose:

Capsaicin:

- Apply 3-4 times/day to the affected area

Diclofenac sodium:

Topical gel:

- Lower limb: Apply 4 g of 1% gel to the affected area 4 times/day; Max. 16 g per joint /day

- Upper limb: Apply 2 g of 1% gel to the affected area 4 times/day; Max. 8 g per joint/day

Note: Maximum total body dose should not exceed 32 g per day

Topical solution – Knee:

- Canadian labeling: Apply 40 drops four times/day or 50 drops three times/day to the affected knee for up to 3 months

- U.S. labeling: Apply 40 drops four times/day to the affected knee

- Betamethasone

- Methylprednisolone acetate (most commonly used)

- Triamcinolone acetonide

- Triamcinolone hexacetonide

Mechanism:

- Decreases inflammation and the normal immune response through multiple mechanisms, also suppresses adrenal function at high dose, also has mineralocorticoid activity

Dose:

Betamethasone: (Intra-articular)

- Hip: 1-2 ml

- Knee, ankle, shoulder: 1 ml

- Elbow, wrist: 0.5-1 ml

- Metacarpophalangeal, sternoclavicular: 0.25-0.5 ml

Methylprednisolone:

(Intra-articular)

- Hip: 80-160 mg

- Ankle, shoulder: 40 mg

- Knee: 40-80 mg

- Elbow, wrist: 20-40 mg

- Small joint like MCP, PIP, DIP, SC: 10 mg

Triamcinolone acetonide:

(Intra-articular)

- Large joints: 5-40 mg

- Small joints: 2.5-10 mg

Triamcinolone hexacetonide:

(Intra-articular)

- Large joints: 10-20 mg

- Small joints: 2-6 mg

Antirheumatic Agent, Viscosupplements

- Sodium hyaluronate

- Hylan GF 20

- Stabilized hyaluronic acid

Mechanism:

- Works as a lubricant and also act as viscoelastic support maintaining a separation between tissues

- Helps in maintaining synovial fluid viscosity

- Supports the articular cartilage in shock absorption

Dose:

Sodium hyaluronate: (Orthovisc, Euflexxa, Neovisc, Hyalgan, Suplasyn)

- Intra-articular: Inject 2 ml every week for 3 weeks

Sodium hyaluronate: (Monovisc)

- Intra-articular: Inject 4 ml once

Hylan GF 20: (Synvisc)

- Intra-articular: Inject 2 ml every week for 3 weeks

Hylan GF20: (Synvisc One)

- Intraarticular: Inject 6 ml once

Stabilized hyaluronic acid: (Durolane)

- Intraarticular: Inject 3 ml once

Serotonin/Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitor

- Duloxetine

Mechanism:

- A potent serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor

- Weakly inhibits dopamine reuptake

- Has a centrally acting analgesic effect; demonstrating pain relief in peripheral neuropathy and fibromyalgia

- Due to its central effect; has now been approved for knee OA

Ref: Chappell AS, Ossanna MJ, et al. Pain. 2009; 46:253-60.

Dose:

Duloxetine

- 60 mg PO once daily; recommended for knee osteoarthritis

- Acetaminophen and Codeine

- Acetaminophen and Oxycodone

- Acetaminophen and Tramadol

Mechanism:

Acetaminophen

- Analgesic action: Likely inhibits the synthesis of prostaglandins in the central nervous system

- Antipyretic action: Inhibits the hypothalamic heat-regulating center

Codeine/Oxycodone/Tramadol

- Bind to opioid receptors in the CNS

- Inhibits reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine in the CNS (tramadol only)

- Also inhibit ascending pain pathways, and alter the perception of and response to pain

Dose:

Acetaminophen and Codeine (#1, #2, #3 and #4):

- 1-2 tablet PO every 4-6 hours as required; Max. 4 g/24 hours based on acetaminophen component (Max. 12 tablets for # 1/2/3 and 6 tablets for # 4)

Acetaminophen and Oxycodone:

- Based on oxycodone content 2.5-5 mg PO every 4-6 hours; Max. 4 g/24 hours based on acetaminophen component

Acetaminophen and Tramadol:

- 1-2 tablets PO every 4-6 hours as needed; Max. 8 tablets/day

[/cq_vc_tab_item][/cq_vc_tabs]

Clinical Trials

- Celecoxib versus omeprazole and diclofenac in patients with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis (CONDOR)

- Gastrointestinal toxicity with celecoxib vs Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: the CLASS study

- Glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate, and the two in combination for painful knee osteoarthritis

Pipeline Agents

Currently unavailable.

Physician Resources

Tips for patient care

Risk factor management:

- Educate patient about triggers and inciting events for OA

- Correction of posture and body mechanics should be implicated by teaching and demonstrating techniques

- Advise to wear appropriate footwear and use assistive devices, if required

- Advise to use appropriate adaptive devices for the performance of activities of daily living whenever necessary

- NSAIDs may promote GI ulceration/bleeding, as well as impair renal function, raise blood pressure, and cause or exacerbate CHF

Monitoring:

- Periodic monitoring of CBC, renal function tests, and blood pressure is important in patients on long term NSAIDs therapy

- Caution regarding complications of NSAIDs, such as

- GI bleeding

- Thrombotic events

- Renal and hepatic toxicity

- Consider concurrent comorbidities when prescribing pharmacotherapy

Medications:

- Advise patient to follow prescribed routine for pill-taking

- In prescribing medication, always evaluate risks and benefits of therapy

- Advise to use only one NSAID at a time (with the exception of low-dose cardioprotective ASA)

- Misoprostol, high dose H2 blockers or proton pump inhibitors are recommended in patients who are taking NSAIDs and are at increased risk for upper gastrointestinal adverse events

- If possible, avoid long term daily use of NSAIDs and opioid analgesics

- Lower starting doses are suggested in elderly and debilitated patients

- Evaluate cost, affordability and insurance coverage for patients

Adaptive devices:

- Discuss available therapeutic options and benefits of adaptive devices with the patient

- Advise use of cane of appropriate height

Alerts:

- Inform patient on NSAIDs that spontaneous GI bleeds may occur. Consider gastroprotection in high-risk patients (age >65, on ASA, prior GI ulcer/bleed)

- Discontinue NSAIDs (except ASA) in patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome

- If required, an opioid analgesic may be used as an alternative for pain control

- COX-2 inhibitors carry a reduced GI risk

- NSAIDs may reduce effectiveness of ACE inhibitors and diuretics in hypertension therapy

Activities (physical, mental, others):

- Emphasize the importance of appropriate exercise, joint protection, strengthening of muscles supporting the joint, as well as activity modification and safety issues to patients

- Advise patients to participate in activities of daily living but avoid overwork and fatigue

- Encourage weight loss to decrease stress on weight-bearing joints

References

Core Resources:

- Compendium of Pharmaceuticals and Specialties (CPS). Canadian Pharmacist Association. Toronto: Webcom Inc. 2012

- Day RA, Paul P, Williams B, et al (eds). Brunner & Suddarth’s Textbook of Canadian Medical-Surgical Nursing. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2010

- Foster C, Mistry NF, Peddi PF, Sharma S, eds. The Washington Manual of Medical Therapeutics. 33rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010

- Gomoll A, Spitzer A, Richmond JC, et al. Repeat administration of triamcinolone acetonide extended-release affords consistent, clinically relevant improvements in pain: results from a phase 3B, single-arm, open-label study. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, Volume 27, S505 – S506. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2019.02.570

- Gray J, ed. Therapeutic Choices. Canadian Pharmacists Association. 6th ed. Toronto: Webcom Inc. 2011

- Katzung BG, Masters SB, Trevor AJ, eds. Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. 11th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2009

- Longo D, Fauci A, Kasper D, et al (eds). Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 18thed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2011

- McPhee SJ, Papadakis MA, eds. Current Medical Diagnosis & Treatment. 49th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2010

- Moskowitz RW, Altman RD, Hochberg MC et al. (2007). Osteoarthritis: Diagnosis and medical/surgical management.(4th ed) Philadelphia:Lippincott Williams and Wilkins

- Pagana KD, Pagana TJ eds. Mosby’s Diagnostic and Laboratory Test Reference. 9th ed. St. Louis: Elsevier-Mosby; 2009

- Skidmore-Roth L. ed. Mosby’s drug guide for nurses. 9th ed. St. Louis: Elsevier-Mosby; 2011

- Skidmore-Roth L, ed. Mosby’s nursing drug reference. 24th ed. St. Louis: Elsevier-Mosby; 2011

- Online resource/weblinks:

- The Merck Manuals

- RheumInfo

- The Arthritis Society, Canada

Online Pharmacological Resources:

- e-therapeutics

- Lexicomp

- Rxlist

- Epocrates Online

- Canadian Guideline for Safe and Effective Use of Opioids for Chronic Non-Cancer Pain

Journals/Clinical Trials:

- Altman R, Asch, E, Bloch D, et al. Development of criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis, classification of osteoarthritis of the knee.ArthritisRheum 1986; 29:1039

- Chan FKL, Lanas A, Scheiman J, et al. Celecoxib versus Omeprazole and Diclofenac in Patients with Osteoarthritis and Rheumatoid Arthritis (CONDOR).The Lancet, 2010;376:173-179

- Chappell AS, Ossanna MJ, et al. Duloxetine, a centrally acting analgesic, in the treatment of patients with osteoarthritis knee pain: a 13-week, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Pain. 2009; 46:253-60

- Clegg DO, Reda DJ, Harris CL, et al. Glucosamine, Chondroitin Sulfate, and the Two in Combination for Painful Knee Osteoarthritis (GAIT). N Engl J Med. 2006;354:795-808

- Evaniew AL, Evaniew N. Knee osteoarthritis: Therapeutic alternatives in primary care. World J Orthop. 2017;8(2):187-191. Published 2017 Feb 18. doi:10.5312/wjo.v8.i2.187

- Kopec JA, Rahman MM, Berthelot JM. Descriptive Epidemiology of Osteoarthritis in British Columbia, Canada 2006; J Rheumatol 2007;34:386-93

- Kraus VB. Pathogenesis and treatment of osteoarthritis. Med Clin North Am. 1997; 81:85-112

- Masuhara, K, Nakai, T, Yamaguchi, K, et al. Significant increases in serum and plasma concentrations of matrix metalloproteinase’s 3 and 9 in patients with rapidly destructive osteoarthritis of the hip. Arthritis Rheum 2002; 46:2625

- Oliveria SA, Felson DT, Reed JI, et al. Incidence of symptomatic hand, hip, and knee osteoarthritis among patients in a health maintenance organization Arthritis Rheum.1995; 38:1134-1141

- Peat G, Thomas E, Duncan R, et al. Estimating the probability of radiographic osteoarthritis in the older patient with knee pain. Arthritis Rheum 2007; 57:794

- Rosenberg ZS, Shankman S, Steiner GC, et al. Rapid destructive osteoarthritis: clinical, radiographic, and pathologic features. Radiology 1992; 182:213

- Silverstein FE, Faich G, Goldstein JL, et al. Gastrointestinal Toxicity with Celecoxib vs Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs for Osteoarthritis and< Rheumatoid Arthritis (CLASS Study). JAMA. 2000; 284:1247-55

- Wong R, Davis AM, Badley, et al. Prevalence of Arthritis and Rheumatic Diseases around the World. A Growing Burden and Implications for Health Care Needs. Arthritis Community Research and Evaluation Unit- Models of Care. 2010